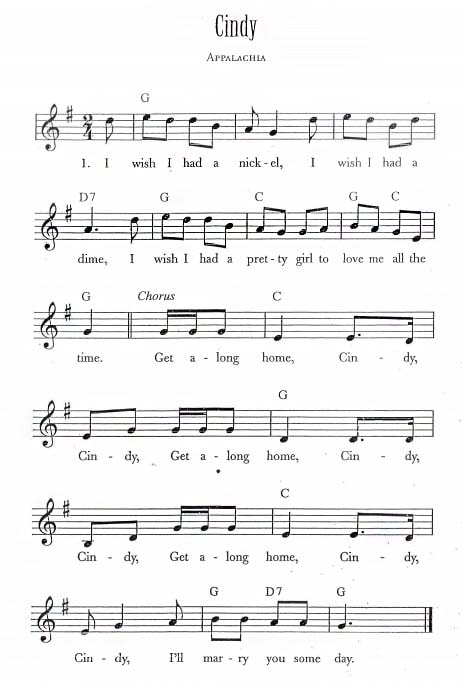

I change it to accommodate my fingers and skill level.

Guilty as charged.

I know. Some of you are reaching for the fainting couch.

Doesn’t matter if it’s Debussy or Billy Strayhorn. I’m putting it in a key that’s . . . convenient. The third movement of Suite bergamasque, "Clair de lune": yeah, it’s in Db but I’m transposing that bad boy and playing it in C (exceptions to the rule: choral accompaniments don’t get a Mulligan and Strayhorn’s “Lush Life” will ALWAYS be in Db).

Maybe you took piano lessons as a kid or only class piano in college. Either way, if you’re honest with yourself, piano is a big part of music education at any level and especially in the elementary music classroom.

Take a moment to examine your relationship with the eighty-eights. When did you start? What compelled you to play – or avoid – the piano.

What’s the first thought you have when hear the sound of a piano?

Joy? Fear? Contentment?

When I hear the piano, I think of my mom’s playing when I was a little kid, Glenn Gould, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Peter Nero, Bill Evans, and Gene Harris, the pianists I heard live as a little kid like Count Basie, Earl Gardner, Bernard Peiffer, and Cy Coleman, the great local pianists I’ve met and got to hear live over the years like Don Glandon and Jeff Knoettner, and the fabulous pianists I played with like Frank Germin, Joe Laird, and Marty Lassman.

Most of all, when I close my eyes and “think” piano, I see the thousands of children I introduced to playing piano.

How you approach piano in front of kids or in the public is not dictated by just your technical proficiency. It also depends on your overall musical confidence and your ability to adapt on the fly, too.

When I approach a piano to play for an audience, I am not concerned with notes. I am focused on how I am going to communicate the emotion and story that I found in the composition.

You might hear a wrong note but you will NEVER hear a specious sentiment.

I didn’t have piano lessons as a kid. I always wanted them. The primary reason was that my parents did not have the required discretionary cash. Although my mother was a childhood prodigy and played on the Horn and Hardart Children's Hour in Philadelphia and New York, she knew her limits with the kid she would be working with and did not attempt to give me piano lessons.

By junior high, my hero was Bill Evans, who was soon joined by Keith Jarrett and Glenn Gould. Did I mention Gene Harris?

My only semester of piano was in college.

If you weren’t a pianist going into music education in college, what was your college piano experience like?

Starting in college, I practiced harmonically analyzing piano music (figuring out the harmonic progressions with emphasis on leading tones and crucial intervals) and re-harmonizing classical as well as pop melodies.

I SLOWLY starting voicing what I saw, edited, and re-voiced until I heard first in my mind and second in my ears what I considered an functional version of the original part.

During my last class piano session, my teacher realized my editing ploy – but confided with me that it was probably a more valuable skill than being a note-perfect reading technician, given the line of work was embarking upon.

I worked on these skills so much that I got to the point where I could do simpler songs in real time. I was always testing my abilities with increasingly harder pieces.

Now, every time I think of a song that I've never played before, I can feel the fingers in my brain falling into certain patterns before I even sit down at the piano. As Glenn said, “One does not play the piano with one's fingers, one plays the piano with one's mind.”

I did this each day in my classroom. My own compositions and improvisations became more complex and harder for me to pull off. For years, I kept this in the classroom and held off attempting it in public on gigs. Anything I played on gigs was locked in before the gig and not done on the fly.

Sure, after listening to my edits, Liszt would laugh, Gounod would groan, and Paganini might get positively postal – but the check was always cashed after I played.

The issue then became ‘how do I voice a baseline, inside parts, and a melody, especially like Bill would’.

I'm still working on it.

I will never have Evan’s dexterity, speed, and command over rootless voicings – but I’ve developed the habit of taking the skills I have and pushing them to the next level so much so that I perform solo piano gigs on a fairly regular basis.

In the classroom, I saw that the simple act of modeling piano playing and reinforcing the idea that playing anything musical is a journey was more important than anything I ever said.

When I wasn’t playing, I talked about playing. I would tell my students that my favorite minutes with a piano or guitar were late at night, quietly playing for myself at home, not working on new, challenging pieces but old favorites.

If, as a music teacher who wasn’t a piano major, you are ever disappointed in your piano skills, I’ll let you in on a secret: we all feel that way. The important things are to

- sit down,

- play,

- make progress,

- enjoy, and

- pass the enjoyment on to our students.

And just like Alan Brandt and Bob Haymes named their classic standard: “That’s All”.

I was lucky as a teacher because even though I taught hundreds and thousands of kids how to play piano, some individually, most of them in a general music class, I never saw myself as a piano teacher. I was just a musician who had a few skills, figured out some patterns, paid attention, made music at the piano, and loved sharing what I knew with others so they could go on their OWN journey.

So yes, along with my thousands of accomplices, guilty as charged – and still doing hard time!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed