Marching!

Clicking sticks and singing while you marched!

Beginning band instruments marching down a school hallway playing their first melodies for enthralled younger students!

Let's face it.

Kids love to make music while they march.

I would always promise my children in kindergarten and first grade that we would be doing a parade with sticks, a drum, and an American flag.

Second grade and third graders would see them and beg to march like they did in previous years.

Fourth graders wanted an official marching band with their brand new shinny instruments.

There were illustrative descriptions of how we were going to line up one behind the other and march “left, right, left, right” through our school, performing for our cafeteria workers, custodians, secretaries, and everybody who can take a second to stop and listen to their music.

Sometimes, it felt like I was channeling Harold Hill, except that I actually knew how to teach music.

When I told the class that it was time for the parade, they were beyond giddy with excitement.

As I started lining up them up, they said, “Where are we going today? Where are we going to march? Who are we going to visit? Where are our sticks?”, to which I responded “What? You thought I was going to give you all that stuff and take you through the school before I could see if you could march “left, right, left, right” in a straight line? Oh no, my little friends, we've got some practice to do – right here in this classroom - before I hand out musical instruments and flags.”

And practice we did.

They clapped their hand – no sticks until they could consistently show me a steady beat.

No flag. We used a rubber chicken at the front of the line. “If I am going to be playing guitar and leading this parade, I don’t want to get poked by an American flag. At least if you bump into me with the chicken, it won’t hurt!”

As most of you who know me already know, there's always a learning curve to every activity I did it in class.

It was “let's learn it, practice it, and then deliver it”.

Eventually, they earned and got those sticks, flags, drums and delivered beautiful music up and down the school hallways, singing and playing their folk songs.

Caution: never do a hallway parade during state testing week.

When staff and kids would stop and listen to our marchers sing a song as they as they went “left, right, left, right”, they would often remark to me later how smoothly the whole activity went.

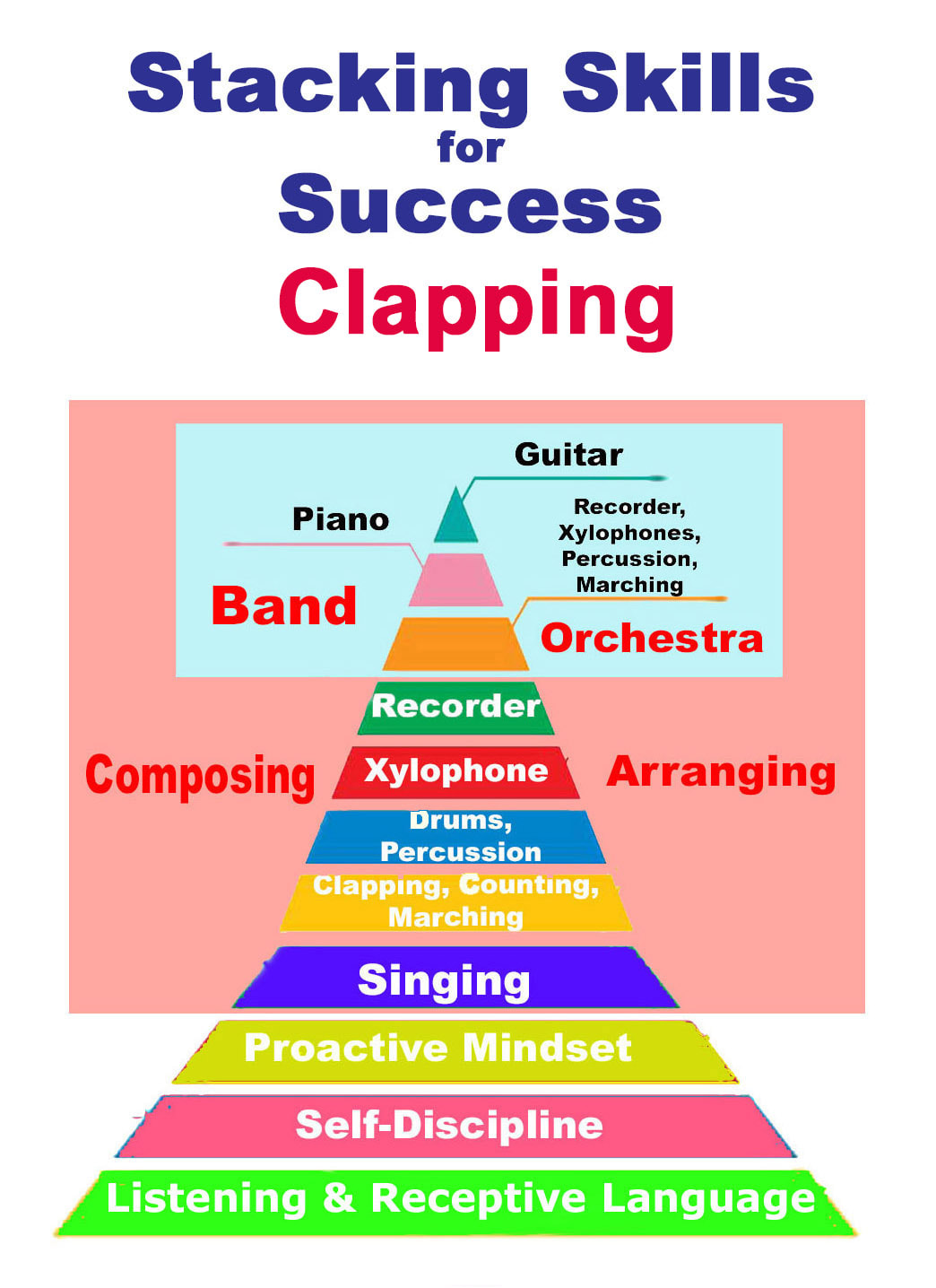

Of course, if you've been reading these posts about stacking skills for success, you already know the secret.

I have been teaching and reinforcing self-discipline, proactivity, and listening skills from week one, day one, class one, minute one.

Teachers who feel like those first three skills can wait because they aren’t as important as getting kids up and running and making music, usually have parades that look more like a crash and burn situation then an orderly parade.

As usual, it's the prep work that makes the activity prosper.

It's what you taught before what you taught that matters.

Marching has a way of reinforcing the idea of making music to a steady beat, first in your feet, then with your hands. It also forces the issue of musically multi-tasking for little kids.

A parade also had a hidden positive effect on a school.

When older kids see the younger students working hard to pull off a parade with instruments and songs, they wistfully think back on how far they themselves have come.

That kind of positive energy can’t be bought – it can only be generated.

And parades work every time!

Check out “Stacking Skills for Success: Marching – Part Two” for a different spin on marching and parades.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed