When you leave home to go to your elementary school in the morning, you always check for your wallet, phone, and keys.

But the keys that you'll need during the day are the different key signatures you'll put your songs in for your students.

You’ll need more than one key.

Since you're in elementary general music teacher, you'll be playing piano and guitar quite a bit. I had a list of somewhere between sixty and a hundred songs that were in steady rotation in my kindergarten through fifth-grade classes. The importance of keys, as in key signatures, is that we need to be able to play all of those songs in at least four or five different keys.

Why? So kids accurately develop their head and chest voices.

I was keenly attuned to the instrument we call our voice at an early age and was one of those kids who was always aware of the difference between my head voice and my chest voice. I would look for ways to disguise either of them to sound like the other. Not all kids are like that.

You’ll have to teach head and chest voice.

Some kids have a deep aversion to singing in their head. Boys are often recalcitrant because they sense a loss of power moving from the chest voice, and, especially in boys, loss of power is not an image they want to project that often.

Of course, it's easy to sing in your head voice with power once you know how to do it. I'm not talking about screaming or yelling but actually singing in a head voice with conviction and assuredness.

It's best to get kids comfortable singing at a moderate volume in their chest voice because it makes the transition to head voice much smoother.

In one of my earlier posts, I listed the five criteria of “big singing”: things I required all kids to do to get a great vocal sound - no screaming, no hands on face, open your mouth, move your lips, and move your tongue.

No screaming is a biggie because sometimes when we are passionate about a song, we just want to belt it out. Occasionally, belting out a song is okay but as music teachers, we can't let it become a habit with our singers.

A song’s tessitura (range) will determine whether kids sing it in their head or chest. Songs with a range of a fifth can usually be sung low in the chest or higher in the head. Things get interesting when the range is more like an octave or more.

But the keys that you'll need during the day are the different key signatures you'll put your songs in for your students.

You’ll need more than one key.

Since you're in elementary general music teacher, you'll be playing piano and guitar quite a bit. I had a list of somewhere between sixty and a hundred songs that were in steady rotation in my kindergarten through fifth-grade classes. The importance of keys, as in key signatures, is that we need to be able to play all of those songs in at least four or five different keys.

Why? So kids accurately develop their head and chest voices.

I was keenly attuned to the instrument we call our voice at an early age and was one of those kids who was always aware of the difference between my head voice and my chest voice. I would look for ways to disguise either of them to sound like the other. Not all kids are like that.

You’ll have to teach head and chest voice.

Some kids have a deep aversion to singing in their head. Boys are often recalcitrant because they sense a loss of power moving from the chest voice, and, especially in boys, loss of power is not an image they want to project that often.

Of course, it's easy to sing in your head voice with power once you know how to do it. I'm not talking about screaming or yelling but actually singing in a head voice with conviction and assuredness.

It's best to get kids comfortable singing at a moderate volume in their chest voice because it makes the transition to head voice much smoother.

In one of my earlier posts, I listed the five criteria of “big singing”: things I required all kids to do to get a great vocal sound - no screaming, no hands on face, open your mouth, move your lips, and move your tongue.

No screaming is a biggie because sometimes when we are passionate about a song, we just want to belt it out. Occasionally, belting out a song is okay but as music teachers, we can't let it become a habit with our singers.

A song’s tessitura (range) will determine whether kids sing it in their head or chest. Songs with a range of a fifth can usually be sung low in the chest or higher in the head. Things get interesting when the range is more like an octave or more.

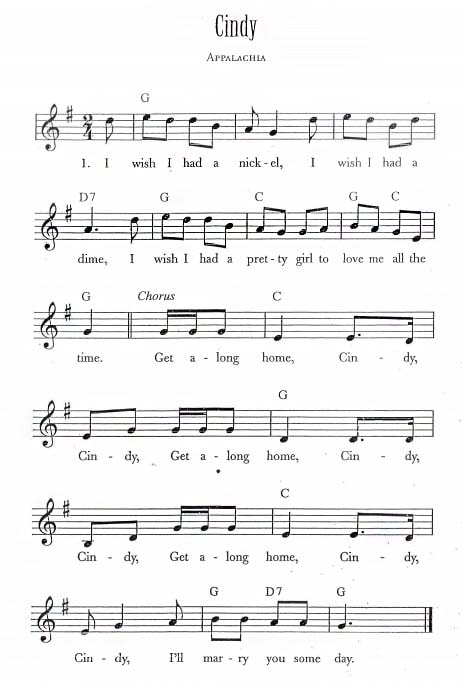

If you take a simple folk songs like “Cindy”, the low note is the third of the scale and the high note is a full octave and a fourth above that!

The verses are primarily high and the chorus is low. When we would sing the first verse, I would usually start it in D, taking the melody down to a F#, which is ridiculously on the low side for elementary voices. In the second verse, I'd move up to Eb or E. On the third verse I go to F, F#, or G and continue to move the keys up with each verse. The effect of ascending keys is that the notes in the chorus section of the song come out stronger but required that the verses are nudged into head voice.

Kids start to learn the difference in voice placement primarily from the form of the song as well as the different ways their voice feels as they hit those different parts of the song.

When we first sang “Cindy”, I would always be at the piano. Eventually I would do the tune on guitar. Given that it's a basic I-IV-V7 song, romping through ascending keys on guitar is very easy. On piano, you have to be able to know how to put the melody on top, a bass part on the bottom, and some kind of inner moving voices in the accompaniment in all the keys.

That's not to say that you play the melody all the time. Including the melody in the piano accompaniment is sort of like training wheels on a bike: you only employ it when they are needed and removed the rest of the time. Otherwise a ubiquitous melody line will function as a crutch and inhibit the young singer’s ability to independently carry a vocal part.

If you are limited on guitar, get a capo to mechanically transpose your comping. More on using a capo will be in another post.

If you're not that proficient on piano yet, start with the basics. First, be able to play the melody in all the diatonic keys. Then play the melody while adding a simple bass ostinato consisting just of the root of the chord. After that, work up to a full throated arrangement.

If you are going to have your kids learn that their voice is an instrument that is just as complex and demanding as a flute or trumpet, you've got to give them the opportunity to visualize and objectify the difference between the techniques and visceral feelings of their head and chest voices.

In the end, one of the greatest gains you'll make is developing a group of confidant, happy singers. The biggest bonus will be empowering boys who know what it's like to be a tenor, especially a boy tenor, who can let those higher notes ring out with no self-conscious fear.

Kids start to learn the difference in voice placement primarily from the form of the song as well as the different ways their voice feels as they hit those different parts of the song.

When we first sang “Cindy”, I would always be at the piano. Eventually I would do the tune on guitar. Given that it's a basic I-IV-V7 song, romping through ascending keys on guitar is very easy. On piano, you have to be able to know how to put the melody on top, a bass part on the bottom, and some kind of inner moving voices in the accompaniment in all the keys.

That's not to say that you play the melody all the time. Including the melody in the piano accompaniment is sort of like training wheels on a bike: you only employ it when they are needed and removed the rest of the time. Otherwise a ubiquitous melody line will function as a crutch and inhibit the young singer’s ability to independently carry a vocal part.

If you are limited on guitar, get a capo to mechanically transpose your comping. More on using a capo will be in another post.

If you're not that proficient on piano yet, start with the basics. First, be able to play the melody in all the diatonic keys. Then play the melody while adding a simple bass ostinato consisting just of the root of the chord. After that, work up to a full throated arrangement.

If you are going to have your kids learn that their voice is an instrument that is just as complex and demanding as a flute or trumpet, you've got to give them the opportunity to visualize and objectify the difference between the techniques and visceral feelings of their head and chest voices.

In the end, one of the greatest gains you'll make is developing a group of confidant, happy singers. The biggest bonus will be empowering boys who know what it's like to be a tenor, especially a boy tenor, who can let those higher notes ring out with no self-conscious fear.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed