|

For more advanced writers: Write a simple song and then turn it into a more complex song. Then do the opposite. Write a complex, dense song and simplify it. It’s a technique I’ve used with great results. No one has to know the original version of your song – just you. What counts is what remains after your editing and re-writing. Which brings me to “Dirty Loops”. If you aren’t familiar with the trio “Dirty Loops”, check them out. When they first broke out, they caught the attention of millions with their covers of Justin’s “Baby, Baby” and Britney’s “Circus”. They took these simple pop songs and re-arranged them into incredible jazz/pop/fusion pieces that were amazingly intricate and opaque.

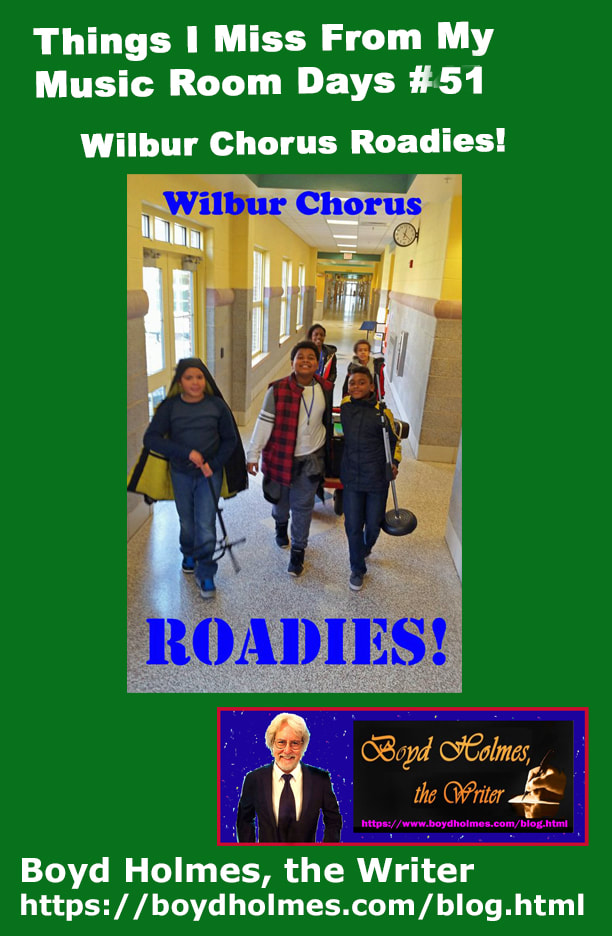

When they started sharing more of their own originals, they shared a songwriting technique. They didn’t start by trying to write something that sounded like a complex “Dirty Loops” cover; they composed a simple pop song and then covered themselves in the style of Dirty Loops. They covered themselves – whaat a concept! They first wrote simple, triadic pop songs that they then re-arranged and injected the “Dirty Loops” DNA in every note, chord, and rhythm. You’d be hard pressed to find the germ motif in their finished products – but it was a necessary part of their writing process. So why not give it a shot. Write something – and then cover yourself. With the tight schedule I was given, I had precious little time to set up for our chorus in the MPR.

I could never have done it without these kids helping me get all our equipment ready for rehearsal. Most typical American wage earners have a good grip on where their money comes from: work, resulting in a pay check.

Where things get murky is what happens to the money after they get it, primarily because many people go through life without creating or living by a budget. They just make payments and buy stuff. And that’s OK if you don’t mind not knowing at all times where your financial ship is on the Ocean of Life. When I was little, every week after I had done all my chores, my father reached into his pocket and gave me a quarter. I didn't start thinking about where that quarter came from for a few years . . . . Musicians are notorious for lax financial habits. We’ve all seen the memes. There is one specific work force that knows were every penny goes is going. Restaurant and bar owners. Their profit margins are slim and anything less than assiduous financial habits can drive their investment into the ground. When you are a gigging musician, you are working for an investor before you are working for a club owner. Everything they spend money on either means more money going out of their pocket or more money staying in their pocket. What they spend on toilet paper, cleaning supplies, potatoes, cocktail napkins, and yes, salaries are always and justifiably under their scrutiny. While many musicians bitch about playing gigs in the 2020s at 1970s wages, they rarely take the club owner’s perspective. That $150 they get at the end of the night comes from somewhere other than a fairy godmother’s satchel like in Cinderella. It comes out of the club owner’s pocket. And aside from the obvious point that you are working to keep the club owner happy, it behooves the gigging musician to embrace the basic idea of where his paycheck originates. It comes from the profits of the club owner. If he doesn’t have an act to pay, that means he has more money to keep in his pocket. As musicians, we have to give them constant reassurance that their investment in us is truly a profitable investment and not ill-conceived charity. One place where club owners get to make a profit and mark up their prices is with alcohol, especially beer. Let’s construct several scenarios focused on beer and hiring an act for $150. Ok. The club owner pays an act $150 for three hours on a Friday night. Where does that $150 come from? FYI, the average markup on beer is 75%. Scenario 1: So, for the sake of discussion, there is no act and a beer is $6. The bar sells 100 beers at $6 per beer . . . $600, right? The cost of the beer, 25% of that $600, is $150. That $150 is out the door. The bar ostensibly pockets $450 (75%) to cover overhead. Scenario 2: There is an act and a beer is $6. The bar sells 100 beers at $6 per beer . . . $600, right? 25% of that $600 is $150. Again, $150 is out the door as the cost of the beer. The bar ostensibly pockets $450 (75%) to cover overhead. So the club pays the act $150 and the beer distributor $150. That leaves the club with $300 . . . 50% profit on beer to pay their overhead. That’s a 25% drop in their profit. Would you be smiling if you lost 25% of your profits? Scenario 3: How about if the bar sells 200 beers and hires an act! 200 beers @$6 a beer = $1200. Cost of the beer = $300 Cost of the act = $150 Profit on beer = $750 (62.5% profit) Scenario 4: How about if the bar sells 400 beers and hires an act? 400 beers @$6 a beer = $2400. Cost of the beer = $600 Cost of the act = $150 Profit on beer $1650 (68.75% profit) Notice how the club owner’s profit on beer is never as high as it was when he/she wasn’t hiring a musical act. Restaurant owners are continuously prioritizing – what to buy, what to pay, what to put on the menu, what to take off. They almost always know their “number” - that is, when they are in the red and when they move into the black. Their number one priority is to stay both afloat and open. Before an act plays a single note, every club has to pay a yearly fee of approx. $1000 to ASCAP for the right to play background music in their club. And since Covid, every club is struggling just to find staff to work in their kitchen and serve food. Back to the beer. In our models, if people drink 3 beers, in order to do the math, Scenario 1 needs 34 customers, Scenario2 requires 67 customers, and Scenario 3 requires 134 customers. Their business gross/profit margins are very slim. They have already paid for ASCAP/BMI house music, a PA system, and/or a digital jukebox lease. There has to be a steady stream of traffic in and out of the club. And it helps if the club is larger than average. You, Mr./Ms. Musician, are there to create more traffic into the establishment. No matter how large the venue is, if the act does not draw people and then keep people in seats longer, which in turns translates into a few more alcohol sales, which turns into more profit margins, which keeps more of the owner’s money in their pocket, it makes no sense for a club to have live music. When you understand this paradigm, things fall into place on gigs and you achieve what we call “flow”. Several months ago, I did a last minute three-hour gig at a restaurant in Old New Castle. When I loaded in, there were about a dozen people in the place. I immediately started asking for requests and played all of them. As more people came in, I edged the volume up to raise the conversation volume level and drop inhibitions a bit. Pro tip: people drink (read: spend and tip), socialize, and laugh more when given a reason to talk louder than they do in their normal setting. I was getting multiple requests for songs as I was playing the previous request. People started facetiming me with their friends, telling them that they need to get to the bar because “this guy is playing everything” and “everyone was there and party was starting”. The bar was exceptionally busy. I didn’t take any breaks – just played continuously. The tips were as steady as the stream of requests. The flow resembled the sustained rush of the Monongahela River. And the requests were mirroring the increasing energy in the room. At the beginning of the third hour, the place was packed and a full-fledged party had broken out. The owner of the club came running up to me. “We’re swamped! You’ve got to play some slow stuff to get some of these people out of here.”, which I did. Mission: accomplished. When we play a bar gig, we need to be armed with knowledge. We are not there to play our five most soul-searching originals or deep cuts by obscure artists. We are there to help the owner achieve their business goals as well as entertain the customers as intensely, relentlessly, and memorably as possible. Anything else is rock and roll fantasy and not business. Your set list is essential to your short and long term musical and financial goals.

Dirty Little Secret #1: it is not YOUR set list; it’s the audience’s set list as well as the club owner’s set list. In our wedding band, all anyone had to say was “Tune selection . . .” and everyone would respond with “is crucial”. You can win over a room of people with the right song at the right time just as easily as you can lose them with wrong song. On a typical three-hour gig, I’ll go through approximately 45 songs. That means the set list I have designed for the gig will easily have 150 songs in it. I always over-prepare. My set list is designed for the clientele that I will be expecting at the gig as well as the expectations of the club owner. It has NOTHING to do with songs that I feel like playing. I am always modifying the set list in real time to accurately reflect the BEST songs I can do in the moment dependent on who is listening to me. I play in a wide variety of venues and that is reflected in my set lists. As a result, the set lists I design for venue#1, venue #2, and venue #3 will often contain NO overlap in tunes. That means I need to know and be able to access 450 tunes on a second’s notice. Knowing and acknowledging the vibe of the venue is important when developing a set list. A set list has to accommodate spontaneous requests from the club owner as well as the customers. For example, the first time I played at an Italian restaurant in lower Delaware, the manager had light instrumental opera playing in the background as I was loading in – that was a first for me! Staying with the vibe, I added intros and outros to some of my songs that were based on light classics: “Girl With the Flaxen Hair”, “Clair de Lune”, "Nessun dorma", “Moonlight Sonata”, Chopin's Prelude in Em, Op. 28 #4. Every time I played one, I got a big smile from Marco, the manager. At one point, he came up and in his thick Italian accent, said, “Your piano sounds fantastic! You gotta play my favorite classic – but I forget the name!” I ran through the opening bits from some Mozart, Beethoven, and Mendelsohn but none of them was the one he wanted to hear. Eventually, he said, “You GOTTA know it, it’s a CLASSIC! It starts . . . “ and then he breaks into full-throated song. “Don’t go changin’!” At that moment, I realized that he was correct. Billy Joel’s “Just the Way You Are” is a classic! I started the intro and immediately Marco started dancing table to table and singing to his customers. Everyone smiled and raised a glass of wine, saluting him as he came by. It was a moment, a moment we repeated every time I played at his restaurant. Picking the right songs and creating the best set list you can is part of a musician’s win/win mindset. Sure, it requires that you learn a lot of material – but in the long run, it’s worth it! I sometimes see social media posts where gigging musicians bemoan what club owners pay.

There are a few variables here. Why are you gigging? For a hobby? For fun? For money? For ego gratification? Equal parts of several options? If you are financially comfortable and just gigging for shiggles and giggles, go for it! Don’t worry about the fee and stop reading right here. If any part of the reason that you’re gigging is for money, are you OK with what you are getting paid? Is gigging fulfilling short or long term financial goals? And no matter what, don’t let your mental axle get wrapped around money, either the money you are paid or that you are tipped. Never use money as a measuring tool for you own musical worth. Try to see everything as the tip jar being half full and not half empty! Gigging is fundamentally about entertaining – don’t let it take on the characteristics of a “cry for help” or an excuse for financial failure. Is gigging your “business”, your “job”, or both and how does it function in your budget? As I have mentioned in other posts, for decades, my finances have been bifurcated: job money and business money. And “gigging” for me encompasses “business” revenue streams including solo gigs, a wedding band, sideman gigs, composer in residence, private teaching, collegiate teaching, designing music/educational software, investing, composing for TV and film, recording, and consulting. I was generating a ton of music and for many years not sleeping a lot! Everyone does this differently. This is how I approached it. In My 40s Before I could put that job money and business money plan into action, I had a lot of credit card debt to pay off and a terrible credit rating. When I got divorced, I assumed all the outstanding debt and it was a lot. For three years, with the exception of my IRA and Roth IRA and a small emergency account I maintained, the goal was to pay off the debt with every penny I could apply to the balance. Everything I bought was paid in cash. These were very lean years. I worked with a financial planner who helped me plot what I would earn through my job and business for every five years until my retirement goal date. With the exception of events of 2001 and 2008, it was pretty accurate. I had something to aim for. I became acutely aware that it is impossible to hit a target if you don’t know what or where the target is. The “job” (public school teacher) was what I did for 7.5 hours five a days a week with a static salary but my “business” was what I did for 16.5 hours five a days a week and 48 hours on weekends and the sky was the limit. I could be a productive or lazy as I wanted to be! I learned how to turn those 16.5 business hours to pay down my debt. I took every opportunity to work and dissolve those revolving charge accounts. No pay check was too small and was always big enough to necessitate a thank you note to the person who hired me. After a few years, I cleared all my debt off the books. I continued hustling and forcing myself to pay my day-to-day out of my business money. If I didn’t make that much during those 130.5 hours every week, guess what - I had to cut back that week, usually on food or leisure. Boiling old bass strings, ramen noodles, three-day-old pizza at the shop down the street, and milk that was less than “fresh” equated to a deeper level of fiscal self-discipline I didn’t realized I possessed. I invested the money from the 38.5 hour a week job in my business. My business was my compounding long-term economic plan. I invested money from my business to help finance my day job master’s degree. After I got the degree, I got a hefty raise in my job. I paid my business back the money I borrowed. I bought a house! I was taking and negotiating increasingly more lucrative solo and wedding band gigs and doing less sideman work where the compensation was static. It meant more work and planning that was not technically related to making sounds on an instrument – contracts, client and venue interaction, always trying to perfect the best set list for gigs, hiring sidemen, etc. but it allowed me to retain more of the fruit of my labors. In My 50s I became more particular with how I booked my business hours. I didn’t take every gig that came down the pike and was still able to max out my IRA and Roth IRA. My job, business, and investment began to gain momentum and take off. The small gigs and the small pay checks (as well as the large ones) I had invested in my early forties had compounded many times over by the end of my fifties. In My 60s I was able to retire from my job at 66 and truly enjoy my retirement totally DEBT FREE. I kept the business going. During covid, I was offered a long term teaching position for a sizable amount. I made a counter offer that was twice as large. They came back with an offer that was $7,000 under my offer. I came back with my original offer. They refused to budge off their second offer. I walked away. And walking away is an acquired skill. It’s acquired by developing a solid financial business plan that results in total financial independence. If You Are Playing Gigs for the Money My way is not the only way – everybody needs to come up with their own plan. The sooner you design, start, and stick to your plan, the happier you’ll be in the long run. A couple of suggestions when looking at the money that club owners are willing to pay: If gigging is not your 7.5 job but rather your 16.5 business . . .

If you find yourself complaining about gig money, find yourself another musician you respect who you can talk to and listen to your feelings. You might have noticed I never said what a good fee for a gig is. That is up to you. If you are happy with the money, you will be happy with the money. If you feel that you are not getting paid enough, that is how you will feel. PLEASE don’t equate what you get paid with self-worth – because it probably won’t work out in your favor. And in the end, it’s not about what you get paid. It’s about what how much of what you get paid is invested and is continuously compounded. Your material music investment should not be based on vanity of any kind. If my material investments didn't return at least a 75% return in two years, I did without and didn't put the money there - no CDs, no videos, no overpriced promotional material. For example, I have designed all my own business cards and stationary over the years. If after decades of gigging, you are able to positively approach your time gigging as an effective way of fulfilling artistic as well as financial goals, you should be debt free or at least close to debt free. By doing the financial and musical homework, you will have had a great career, created a strong business, made life-long friends, played fun gigs, and generated a ton of great memories to look back on. Plus you’ll know a hell of a lot of songs! |

AuthorBoyd Holmes, the Writer Archives

June 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed