In a previous post, I focused on melodic rhythm and how understanding it in your lyrics can help propel your work.

I’ve also emphasized how the shorthand system of notation called a lead sheet is, as they say in advertising work, a “fast and dirty” way to get your ideas on paper.

Here is a morphing of these two ideas: a Morse Code system to visualize your lyric’s rhythms.

As you might now, Morse Code is a way of using “dots” (short sounds/symbols) and “dashes” (long sounds and symbols) to represent letters of the alphabet.

As a kid, I was way into scouting, electronics, and Morse Code. I saved my pennies and mail ordered a Heath Kit Morse Code oscilloscope that I assembled with a soldering iron. It was a practice device and didn’t send the code anywhere other than the four walls of my bedroom. I became proficient in using the code, loved sending messages into the either, and fantasized about tapping coded communiqués from behind enemy lines and saving the day.

Yeah, I was that kid.

In any case, I lived in a world of notes, dots, and dashes.

Years later, as I worked on my own melodic rhythms, I noticed the parallels between the code and the aspect of short and long notes.

If you analyze most melodic rhythms, there’s nothing fancy. It usually boils down to short sounds and long sounds, with a few gradations in-between.

One day, I decided not to write my melodic notations in traditional rhythmic notation on manuscript paper but rather just put down the dots and dashes on blank paper reflecting the relative length of the notes.

Several things happened.

I realized that notation is small and my dots and dashes on a 8.5x11 inch pages were big. I thought back to stories about the quirky American composer Charles Ruggles who coined the term "dissonant counterpoint ".

When he composed, he often didn’t use conventional staff paper.

Instead, he would horizontally paper the walls of his rooms ceiling to floor with rolls of huge manuscript shelving paper where the lines of the staff were an inch a part.

I found that when it came to lyrics, I worked better with larger iconography rather than with tiny notes on a staff. (To this day, when I create PDFs of lyrics, I have tiny margins and enlarge the font as big as possible. I put as much of the page’s canvas into play. This also pays infinite dividends when giving lyrics to kids. Big is good.)

I also realize I was turning my back on what I was taught to do- specifically use notation to get my ideas a sprecise and “correct” as possible.

I was thinking less like a college graduate with a degree in music and more like a kid with a mail order Morse Code oscilloscope.

Sometimes retrograde re-tooling is what’s called for.

Did I have the musical chops to write out my rhythms? Of course.

But sometimes the conventional approach is not the best for achieving flow and maximizing visualization.

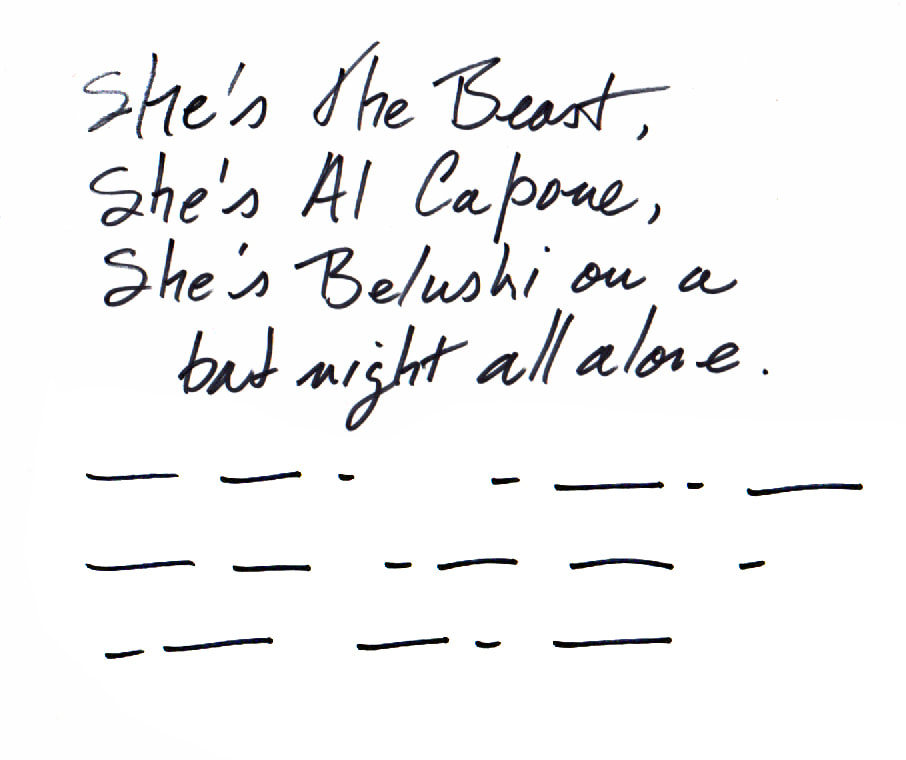

Here is an example of how I do it. These are the first few lines of a song of mine, “The Beast” with the prose on top and the code on the bottom.

I’ve also emphasized how the shorthand system of notation called a lead sheet is, as they say in advertising work, a “fast and dirty” way to get your ideas on paper.

Here is a morphing of these two ideas: a Morse Code system to visualize your lyric’s rhythms.

As you might now, Morse Code is a way of using “dots” (short sounds/symbols) and “dashes” (long sounds and symbols) to represent letters of the alphabet.

As a kid, I was way into scouting, electronics, and Morse Code. I saved my pennies and mail ordered a Heath Kit Morse Code oscilloscope that I assembled with a soldering iron. It was a practice device and didn’t send the code anywhere other than the four walls of my bedroom. I became proficient in using the code, loved sending messages into the either, and fantasized about tapping coded communiqués from behind enemy lines and saving the day.

Yeah, I was that kid.

In any case, I lived in a world of notes, dots, and dashes.

Years later, as I worked on my own melodic rhythms, I noticed the parallels between the code and the aspect of short and long notes.

If you analyze most melodic rhythms, there’s nothing fancy. It usually boils down to short sounds and long sounds, with a few gradations in-between.

One day, I decided not to write my melodic notations in traditional rhythmic notation on manuscript paper but rather just put down the dots and dashes on blank paper reflecting the relative length of the notes.

Several things happened.

I realized that notation is small and my dots and dashes on a 8.5x11 inch pages were big. I thought back to stories about the quirky American composer Charles Ruggles who coined the term "dissonant counterpoint ".

When he composed, he often didn’t use conventional staff paper.

Instead, he would horizontally paper the walls of his rooms ceiling to floor with rolls of huge manuscript shelving paper where the lines of the staff were an inch a part.

I found that when it came to lyrics, I worked better with larger iconography rather than with tiny notes on a staff. (To this day, when I create PDFs of lyrics, I have tiny margins and enlarge the font as big as possible. I put as much of the page’s canvas into play. This also pays infinite dividends when giving lyrics to kids. Big is good.)

I also realize I was turning my back on what I was taught to do- specifically use notation to get my ideas a sprecise and “correct” as possible.

I was thinking less like a college graduate with a degree in music and more like a kid with a mail order Morse Code oscilloscope.

Sometimes retrograde re-tooling is what’s called for.

Did I have the musical chops to write out my rhythms? Of course.

But sometimes the conventional approach is not the best for achieving flow and maximizing visualization.

Here is an example of how I do it. These are the first few lines of a song of mine, “The Beast” with the prose on top and the code on the bottom.

I did this “dot and dash” drawing with the entire first verse after I nailed down the lyrics and melodic rhythm.

Before I started the second verse, I put the first verse lyrics aside used the code to repeatedly scat the first verse’s rhythm, sometimes even tapping my finger on each dot and dash as I scatted. I wanted that rhythm to be as automatic that I didn’t have to think about it when I moved onto the next verses.

As I worked on subsequent verses, I would quickly jot the dots and dashes on a blank page and write the next set of lyrics under the markings. I had established my rhyme scheme in the first verse so completing the next verses was easy.

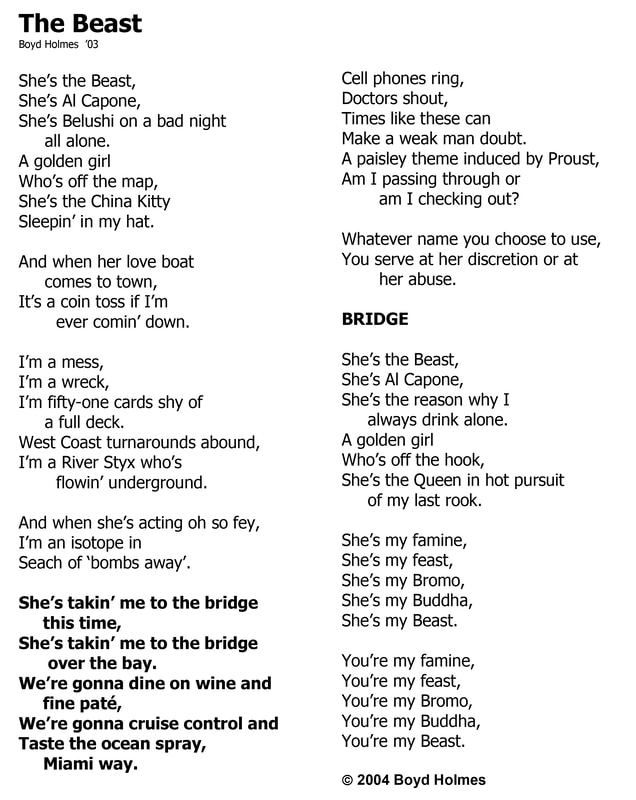

Here’s the complete lyric.

Before I started the second verse, I put the first verse lyrics aside used the code to repeatedly scat the first verse’s rhythm, sometimes even tapping my finger on each dot and dash as I scatted. I wanted that rhythm to be as automatic that I didn’t have to think about it when I moved onto the next verses.

As I worked on subsequent verses, I would quickly jot the dots and dashes on a blank page and write the next set of lyrics under the markings. I had established my rhyme scheme in the first verse so completing the next verses was easy.

Here’s the complete lyric.

One note: I didn’t show you all the subsequent versions and editions I made for each verse. They were beautifully messy with lots of cross outs and arrows pointing to different words. What I have supplied you with is a basic idea, the slightest of suggestions that you can develop in ways that resonate specifically with you and your work habits.

Once again, proof that there is more than just one way to get to the skinny and fat bar line at the end of the song.

Once again, proof that there is more than just one way to get to the skinny and fat bar line at the end of the song.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed