By now, I hope you are seeing that “moving the pencil” is indicative of learning how to audiate both melody and harmony in real time.

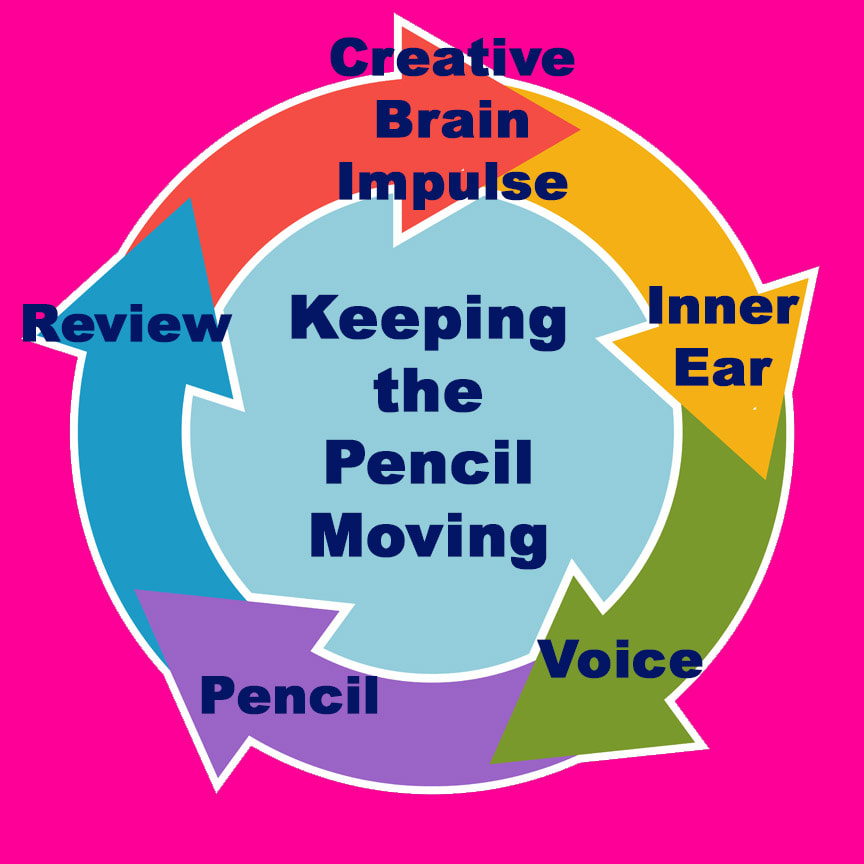

This diagram is how I think I developed the skill of audiation with a pencil. Each step started like an individual cell of a cartoon that gradually sped up to the point that there were no small isolated steps but rather one continuous movement, a lingua franca to experiencing musical sound.

This diagram is how I think I developed the skill of audiation with a pencil. Each step started like an individual cell of a cartoon that gradually sped up to the point that there were no small isolated steps but rather one continuous movement, a lingua franca to experiencing musical sound.

As with much in music, repetition is key in acquiring these skills.

The example we’ve done are all in the key of C major. There are another eleven major keys to become facile in with your pencil – as well as your inner ear.

Just as you probably learned how to run basic eighteenth century harmonic progressions in theory classes, those seminal I-IV-V7 sounds are only the beginning of audiation.

As it becomes increasingly easier to write melodies when you are steadily feeding new and different melodies to your memory, your vocabulary of harmonies has to grow as well.

There are theories that when perfect pitch develops in a young child, one of the greatest influences is continuous exposure to both tonal and atonal melodies and harmonies.

Most of us grow up in a society where traditional harmony rules the day. The more you are able to approach those melodic and harmonic concepts as a child in a play-like way of endless experimentation, the more you can experience and embrace "outside" harminies and melodies, the more supple your audiation skills will become.

As a first year double bassist, I remember reading a bass column in the jazz magazine Downbeat where the author claimed that he had learn a thousand songs by memory. I couldn’t believe that I would ever have that kind of knowledge or ability. The focus of the article was on common progressions and typical, predictive patterns in melodies.

While most of us distinctly remember the particulars of our first kiss or when we learned how to ride a bike, audition skills have a way of creeping up on us.

With supple audiation skills and a good memory, a thousand songs isn't an unreasonable possibility.

One day you are struggling to “hear” and gradually you realize that everything you hear is a variant of something you’ve heard before . You are able to synthesize your past listening experiences with new creative input.

For me, audiation used to be sequential procedures that at first were like a toddler learning how to get around their world: crawl, stand, step, walk, run.

We don’t remember our first independent successes at crawling – but our parents do. I saw my teddy bear across the room and suddenly had a deep desire to hold it so I started to crawl.

Being prepared for the significant motivation was the key for me crawling as well as audiating: I wanted to do it because it gave me pleasure. I wanted it and was willing to make sustained efforts to achieve my goal.

In college, many of my classmates had to learn how to audiate on command. First and foremost, it was required for a grade.

Audiating for me started when I was a toddler when everything was a new experience and my world grew exponentially because of my developmental curiosity.

Just like a lot of early childhood, audiation was messy, not always a straight line of success or growth, lacked a vocabulary, but ultimately fulfilling.

By the time I got to college, I was spending hours pounding on a practice room piano, exploring more complex and textured melodies and harmonies. They stayed with me after I left the practice room.

If you are working to develop your audiating skills, the best advice I can give you is that maybe you might want to “play” instead of “work’. As my friend Jack Jadach would say, “call off the dogs” and let the action progress more from a place of experimentation and play.

That’s not to say that as an adult, programing your time to a goal is different than a child at play.

At it’s core when I was a child, music and audiation was fun for me – and lucky for me, it still is.

The example we’ve done are all in the key of C major. There are another eleven major keys to become facile in with your pencil – as well as your inner ear.

Just as you probably learned how to run basic eighteenth century harmonic progressions in theory classes, those seminal I-IV-V7 sounds are only the beginning of audiation.

As it becomes increasingly easier to write melodies when you are steadily feeding new and different melodies to your memory, your vocabulary of harmonies has to grow as well.

There are theories that when perfect pitch develops in a young child, one of the greatest influences is continuous exposure to both tonal and atonal melodies and harmonies.

Most of us grow up in a society where traditional harmony rules the day. The more you are able to approach those melodic and harmonic concepts as a child in a play-like way of endless experimentation, the more you can experience and embrace "outside" harminies and melodies, the more supple your audiation skills will become.

As a first year double bassist, I remember reading a bass column in the jazz magazine Downbeat where the author claimed that he had learn a thousand songs by memory. I couldn’t believe that I would ever have that kind of knowledge or ability. The focus of the article was on common progressions and typical, predictive patterns in melodies.

While most of us distinctly remember the particulars of our first kiss or when we learned how to ride a bike, audition skills have a way of creeping up on us.

With supple audiation skills and a good memory, a thousand songs isn't an unreasonable possibility.

One day you are struggling to “hear” and gradually you realize that everything you hear is a variant of something you’ve heard before . You are able to synthesize your past listening experiences with new creative input.

For me, audiation used to be sequential procedures that at first were like a toddler learning how to get around their world: crawl, stand, step, walk, run.

We don’t remember our first independent successes at crawling – but our parents do. I saw my teddy bear across the room and suddenly had a deep desire to hold it so I started to crawl.

Being prepared for the significant motivation was the key for me crawling as well as audiating: I wanted to do it because it gave me pleasure. I wanted it and was willing to make sustained efforts to achieve my goal.

In college, many of my classmates had to learn how to audiate on command. First and foremost, it was required for a grade.

Audiating for me started when I was a toddler when everything was a new experience and my world grew exponentially because of my developmental curiosity.

Just like a lot of early childhood, audiation was messy, not always a straight line of success or growth, lacked a vocabulary, but ultimately fulfilling.

By the time I got to college, I was spending hours pounding on a practice room piano, exploring more complex and textured melodies and harmonies. They stayed with me after I left the practice room.

If you are working to develop your audiating skills, the best advice I can give you is that maybe you might want to “play” instead of “work’. As my friend Jack Jadach would say, “call off the dogs” and let the action progress more from a place of experimentation and play.

That’s not to say that as an adult, programing your time to a goal is different than a child at play.

At it’s core when I was a child, music and audiation was fun for me – and lucky for me, it still is.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed