I maintained that if you structure your classes and activities properly, during the daily course of duties, it is pretty clear to see which kids have a grasp on what skills and to what degree they understood them without asking questions.

The most cogent music assessment or question you can a kid is, “Can you play me a song?” For starters, you are signaling that making music comes first. Any additional talking and assessing can wait. All those boorish questioning tones start to resemble at best a post mortem and at worst pure BS. They reveal an adult’s inability to shut their mouth and allow a child to make uninterrupted music.

What’s even worse, I have witnessed teachers ask questions in blatantly rude and pandering ways that immediately demonstrate to the child that it is not the question or answer is not as important as the teacher’s real message: who's the boss.

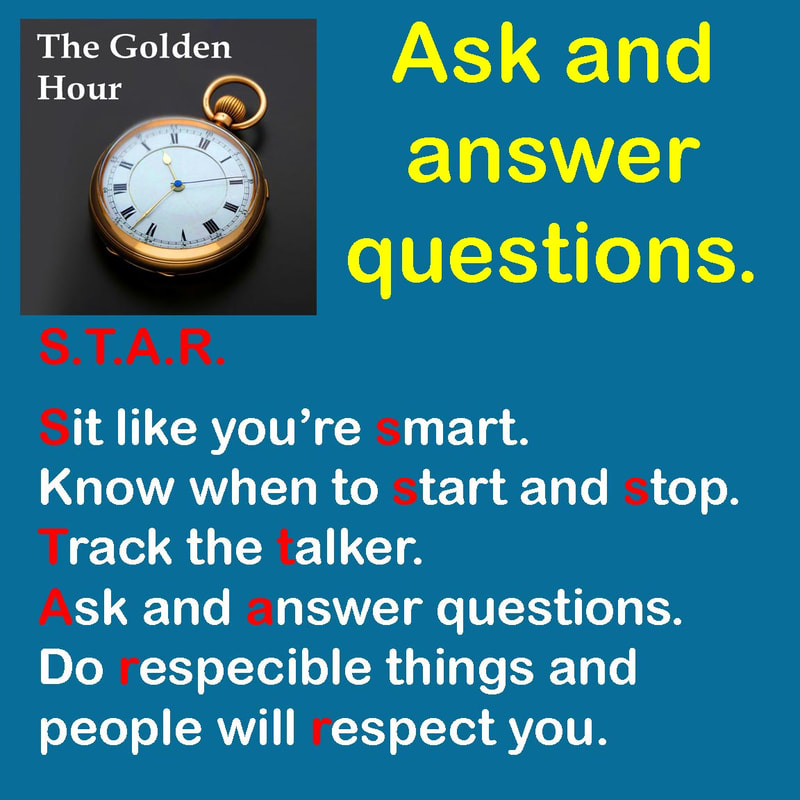

As teachers, we need to encourage children to ask questions of each other as well as of teachers. I would often say, “If I wasn’t here, who would you ask?” There was a sign on our chalkboard: “C3B4Me” – as in “If you have a simple question one of your friends might know the answer, talk to three of them before you ask me.”

C3B4Me was designed for mundane, housekeeping, mechanical activities of our class. In other words, if you see your classmates doing something that you have no clue about, better to ask them first.

When I worked at a school with children with profound disabilities, I became adept it having both sides of the conversation in my quadrant. If a child was primarily nonverbal, I learned how to phrase questions as well as respond to them. For example, as in when a child was looking at my strumming hand , I might infer that he was thinking about my guitar pick. “Boy, I bet you're thinking that guitar pick is really easy to drop, and I have to tell you, it is. It's so easy to drop that I put stuff on my fingers called ‘Gorilla Snot’ so that my pick sticks to my fingertips.”

In my general music classes, some kids would be intimidated by a 6’5” male teacher and less likely to ask questions, especially if they were taking the C3B4Me way too close to heart. I would pepper what I said in class with phrases like “You might be asking yourself why does that dotted quarter note followed by the eighth note sound suspiciously like the dotted eighth note followed by a sixteenth, and that would be a great question. Is anybody thinking that question?” As hands went up, I would call on someone and say “Why don't you ask me that.” It was a low stress way for me to encourage kids to ask without fear or favor.

There were times where a great question from a student resulted in complementary guitar pick, with the expectation that I would never forget that question or the answer that we found together. It was much like when my sixth grade trumpet teacher, Mike Gibson, asked me out of the blue in my trumpet lesson “Sophia Loren or Gina Lollobrigida?”

While it’s important to ascertain what students know, it is even more important to know what they think, how they came to their decisions, and what does their knowledge leads them to: to know what they are bringing to the party, what they can already do.

As music educators, we need to remember that we were formed by the questions we asked and the answers we were given as much as by the questions we were asked and the answers that were expected.

The questions we ask as teachers will model how our students shape their own questions and develop their curiosity toward what is important to them. Assessment and data are not intrinsically bad things but they are not the most important information that we need to pursue with our students.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed