There are seven distinct examples of where I took advantage of visual opportunities to accelerate a student understanding of self-discipline in our room.

People see much more than they hear so I didn’t say anything when I observed something I liked during a class.

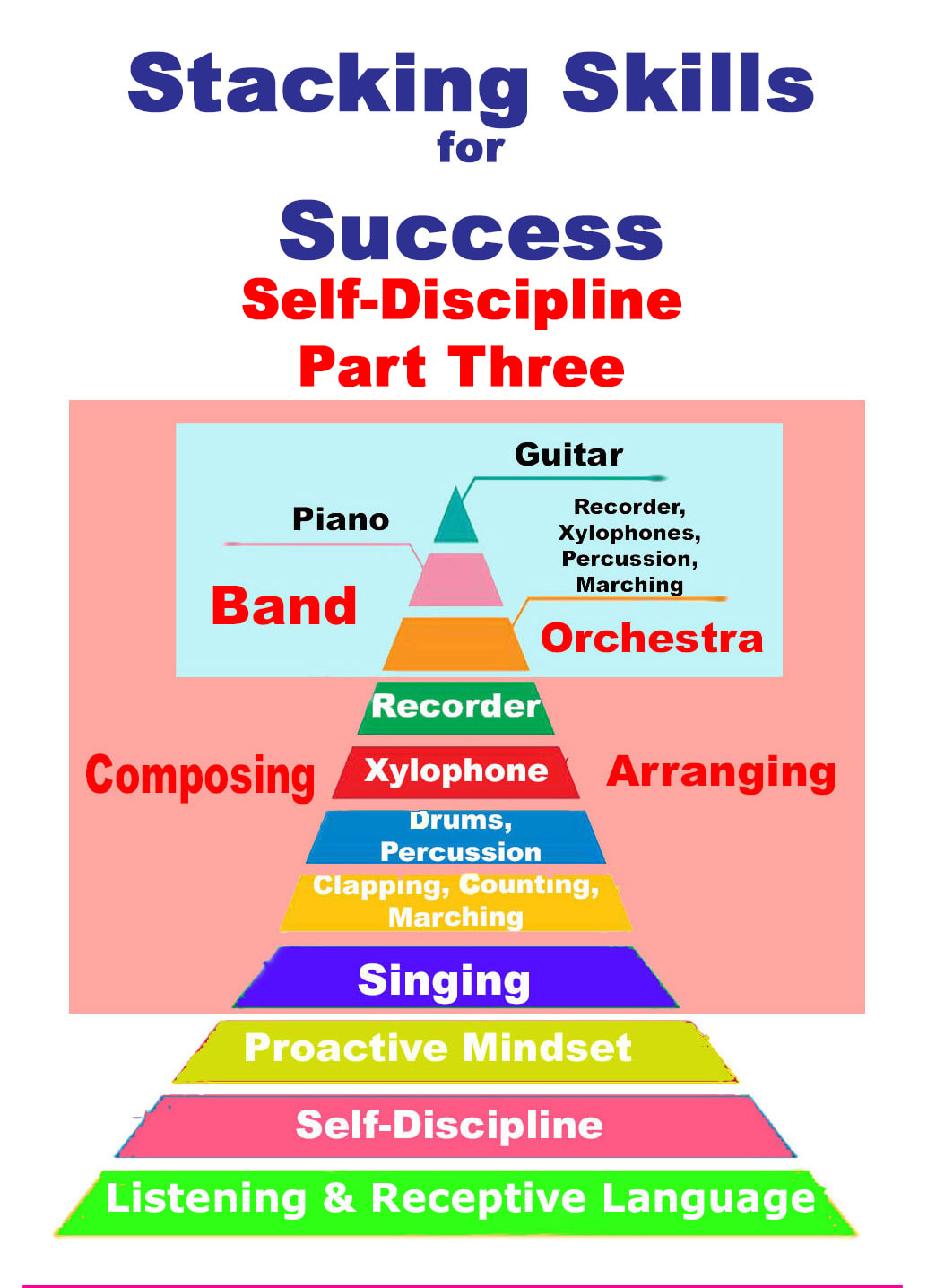

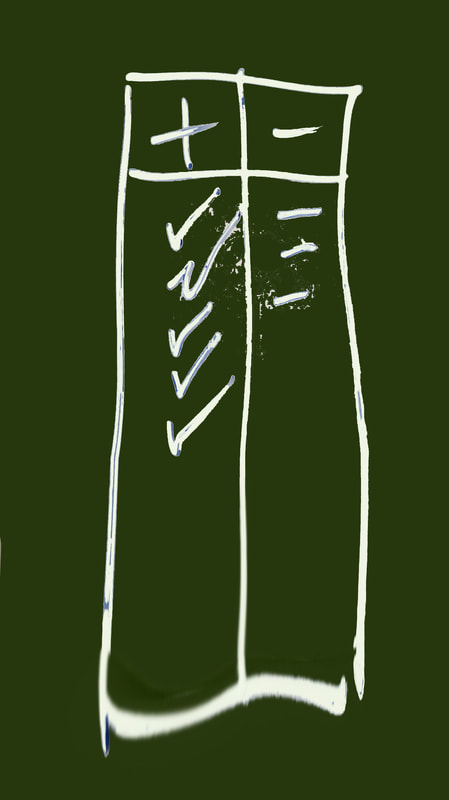

I put a check under the plus sign on my chalkboard. (visual 1)

Conversely, when I saw things that I didn't like, I would put a minus and rarely say anything else. (visual 2)

Sure, I would glare and I might put my hands on my hips and be silent for a few seconds, and try and give them that look of shame, (visual 3) but as far as laying into them and giving them ninety seconds of berating language, I didn't roll that way.

At the end of any teacher’s screed, there's a moment where everyone in the room is disheartened.

Students, especially the ones that didn't partake in any negative behaviors, are ticked off.

The teacher, if they're worth anything, will feel shame for having a spewed language that probably wasn't necessary.

If the class had no clue why they received the plus or minus, I would tell them the source of my feedback.

I found that if I saw the pace of positive things accelerate, I put checks up I put check up at a corresponding rate. (visual 4) When this happened, kids responded . . . . , you guessed it, positively.

At the end of class, the balance sheet would be rectified like a check book (visual 5) with the negatives deducted from the positives, because one thing every child needs to learn is nothing is free.

For every minus I erased, I also erased a plus. (visual 6)

As the kids said, “The good ones pay to get rid of the bad ones”.

If the process started out with more pluses than minuses, the reality of squandering our profits was reinforced.

If we ended the class with more minuses than pluses, that resulted with a net lose.

As Ernest Lawrence Thayer said, “There was no joy in Mudville” on days like that when their teacher came to pick them up.

There would often be no “So Long” song, no “Rotten Pumpkin Potpourri” room spray as they left the room, and worst of all, no smiles as they silently left the room.

I would tell the classroom teacher of their poor choices and ask the kids what they did differently than they did on a day when they earned ten pluses. I would write down what they said and visually post those better choices on the chalk board before their next class began as a reminder. (visual 7)

Our bad choices will often penalize our good intentions and we have to learn that with the fewer bad choices we make, we will have more good things at the end of the day.

The amount of positives that classes earned would often be the subject for conversation as we were getting ready to leave class.

“Wow, you guys did even better than Ms. Smith's class. They only had twelve pluses. You had seventeen!”

Or “I can't wait to tell your teacher how well you did today and how many pluses you got. And whatever you do, don't tell her about the minuses. You paid them off with your pluses so those minuses don't exist anymore. They're just between you and me. She'll only know that you got seventeen pluses today.”

“Yeah, wouldn't that be cool, to get 22 pluses?”

In my next post, I'll describe a foolproof system for helping your kids know when to talk and when to be quiet. That'll be in “Stacking Successes: Self-Discipline - Part 4.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed