As music educators, our day is made up of classes that in turn are made up of segments that begin to resemble seven-minute snippets of presentation.

There's that “Hello Song”. And the “So Long Song”. And then the xylophone bits, piano bits, guitar bits, and then there's learning new songs and the list never ends.

Dr. Stephen Covey cites “sharpen the saw” as one of his habits of highly effective people. It reminds us to review, renew, and refresh all aspects of our personal and professional lives.

Keep the blade sharp. Don’t let it get dull.

I was always trying to sharpen the saw of my teaching.

Over all the decades of teaching that I’ve done, it all boils down to hundreds of seven-minute anchor bits that presented my content and emphasized my core value system over and over to students.

Years ago, I heard an interview with Jerry Seinfeld and how he got his big break. As his story unfolded, it resonated in my head like an atomic bomb going off. He was telling my story. Let me attempt to tell his story first.

Before all his fame and fortune, Jerry Seinfeld was a working comedian. As his reputation on the comedy circuit grew, so did his bookings and renown. One day his manager contacted him and exclaimed, “You've done it, you've hit it! They want you next week on the Tonight with Johnny Carson!”

At that time, the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson was the pinnacle of success for any stand-up comedian. It was what you did before you were on the cover of Time magazine.

To his manager’s consternation, Seinfeld told him to postpone the booking. He would tell this manager when the time was right.

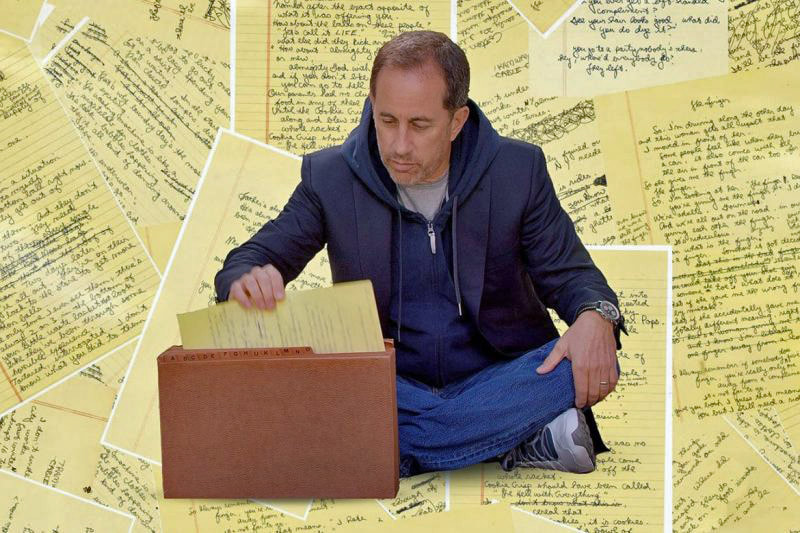

Seinfeld went home and poured over hundreds of yellow legal pad pages of comedy material he had written, put together the best seven minutes he could, and started rehearsing them. He went to comedy clubs in New York City every night for months performing the same seven minutes over and over for a different crowd of tourists each night.

There's that “Hello Song”. And the “So Long Song”. And then the xylophone bits, piano bits, guitar bits, and then there's learning new songs and the list never ends.

Dr. Stephen Covey cites “sharpen the saw” as one of his habits of highly effective people. It reminds us to review, renew, and refresh all aspects of our personal and professional lives.

Keep the blade sharp. Don’t let it get dull.

I was always trying to sharpen the saw of my teaching.

Over all the decades of teaching that I’ve done, it all boils down to hundreds of seven-minute anchor bits that presented my content and emphasized my core value system over and over to students.

Years ago, I heard an interview with Jerry Seinfeld and how he got his big break. As his story unfolded, it resonated in my head like an atomic bomb going off. He was telling my story. Let me attempt to tell his story first.

Before all his fame and fortune, Jerry Seinfeld was a working comedian. As his reputation on the comedy circuit grew, so did his bookings and renown. One day his manager contacted him and exclaimed, “You've done it, you've hit it! They want you next week on the Tonight with Johnny Carson!”

At that time, the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson was the pinnacle of success for any stand-up comedian. It was what you did before you were on the cover of Time magazine.

To his manager’s consternation, Seinfeld told him to postpone the booking. He would tell this manager when the time was right.

Seinfeld went home and poured over hundreds of yellow legal pad pages of comedy material he had written, put together the best seven minutes he could, and started rehearsing them. He went to comedy clubs in New York City every night for months performing the same seven minutes over and over for a different crowd of tourists each night.

Everytime he presented the material, he kept mental notes of what he changed to make his material funnier and work better. A raised eyebrow here, a hand on a hip there. He dropped words, he added gestures. He got it so those seven minutes were tighter and tighter with each presentation.

The next line from the interview was the line I'll never forget because it's the image that resonated so deeply with me and my teaching.

In a matter-of-fact-tone, Jerry said after doing the same seven minutes over and over and editing them to be stronger and funnier, it got to the point where his routine was so good and the audience was howling so continuously, that a woman could have walked up on stage, slapped him in the face, and no one would have noticed. That's how effective his material worked.

When Jerry felt the seven minute set had solidified into comedy gold, he contacted his manager and told him to book the Tonight Show. He was on the next week, did his seven minute set, killed, and the national and international phenomenon we know of as Jerry Seinfeld was born.

Jerry was describing my life as a music teacher: establishing core material, presenting, taking data, editing, practice, present, collect data, edit, practice, and so on until I found the best combination of content, timing, pacing, and could stick the landing every time at the end of the teaching segment.

I was collecting data on audio and video, looking for what was strong, deleting what was weak, searching for bad – and good - patterns that were in my presentations.

And always edit. Edit, edit, edit.

Take away question: What “bits” of your classes could you edit to make them more effective?

I discovered that one of the greatest gifts you can give your classes is a tightly-edited framework that they can accurately predict from week to week.

I crafted my classes so they had well-defined and predictable beginnings, middles, and ends.

The beginnings of my class we're tightly patterned, scripted, and staged as the kids came in and did our “Hello Song”. As we transition from activity to activity, the “Go” times, started to resemble commercial breaks.

At the end of class, the “So Long Song”, with my “I’ll see you . . . next time . . . at Music!” was so effective a resolution that the kids would often jump up and just clap their hands, not necessarily for me but for themselves and for what they had just done.

Take a look at your work.

All those seven-minute segments in your 7.5 hour job - could they benefit from an editor’s pen?

Are there phrases you could tighten up?

A lower voice here, a pause there?

A term that we used in my 16.5 hour business (AKA rock band) was a “tight forty-five”, meaning that for a forty-five minute set, every second was tightly packed with music, with very little opportunity for the audience’s attention to drift.

Teaching started to resemble that mindset for me. One gig a day, six sets a gig, forty-five minute sets. My goal during my 7.5 hour teaching day was similar to that of a rock gig: to close even stronger at the end of the day then I started at the beginning.

Jerry Seinfeld’s story was an affirmation, a confirmation that I had been on the right track, that there was always room for improvement and editing, that a tight forty-five minute class had to include some laughs in it, too, because music is nothing if it doesn't travel through your heart and sometimes makes you laugh or cry.

Take away: I love watching teachers who have made the effort to consciously edit their material to make it more potent in the classroom. Conversely, it’s painful observing a teacher who is on “rote mode” or “winging it mode”.

Lesson plans are for admin. Scripts are for pros. I remember showing a brief lesson plan to a principal but then showing her pages of script that I had written in support of the plan. She said she had never seen that kind of preparation before. I told her the Seinfeld story and she “got it”.

My mother had an old note pad. On the top of each page was the phrase, “Don’t say it. Write it.”

When in doubt, edit.

Let the guy who created the show about nothing remind us that EVERYTHING can get better . . . with editing.

The next line from the interview was the line I'll never forget because it's the image that resonated so deeply with me and my teaching.

In a matter-of-fact-tone, Jerry said after doing the same seven minutes over and over and editing them to be stronger and funnier, it got to the point where his routine was so good and the audience was howling so continuously, that a woman could have walked up on stage, slapped him in the face, and no one would have noticed. That's how effective his material worked.

When Jerry felt the seven minute set had solidified into comedy gold, he contacted his manager and told him to book the Tonight Show. He was on the next week, did his seven minute set, killed, and the national and international phenomenon we know of as Jerry Seinfeld was born.

Jerry was describing my life as a music teacher: establishing core material, presenting, taking data, editing, practice, present, collect data, edit, practice, and so on until I found the best combination of content, timing, pacing, and could stick the landing every time at the end of the teaching segment.

I was collecting data on audio and video, looking for what was strong, deleting what was weak, searching for bad – and good - patterns that were in my presentations.

And always edit. Edit, edit, edit.

Take away question: What “bits” of your classes could you edit to make them more effective?

I discovered that one of the greatest gifts you can give your classes is a tightly-edited framework that they can accurately predict from week to week.

I crafted my classes so they had well-defined and predictable beginnings, middles, and ends.

The beginnings of my class we're tightly patterned, scripted, and staged as the kids came in and did our “Hello Song”. As we transition from activity to activity, the “Go” times, started to resemble commercial breaks.

At the end of class, the “So Long Song”, with my “I’ll see you . . . next time . . . at Music!” was so effective a resolution that the kids would often jump up and just clap their hands, not necessarily for me but for themselves and for what they had just done.

Take a look at your work.

All those seven-minute segments in your 7.5 hour job - could they benefit from an editor’s pen?

Are there phrases you could tighten up?

A lower voice here, a pause there?

A term that we used in my 16.5 hour business (AKA rock band) was a “tight forty-five”, meaning that for a forty-five minute set, every second was tightly packed with music, with very little opportunity for the audience’s attention to drift.

Teaching started to resemble that mindset for me. One gig a day, six sets a gig, forty-five minute sets. My goal during my 7.5 hour teaching day was similar to that of a rock gig: to close even stronger at the end of the day then I started at the beginning.

Jerry Seinfeld’s story was an affirmation, a confirmation that I had been on the right track, that there was always room for improvement and editing, that a tight forty-five minute class had to include some laughs in it, too, because music is nothing if it doesn't travel through your heart and sometimes makes you laugh or cry.

Take away: I love watching teachers who have made the effort to consciously edit their material to make it more potent in the classroom. Conversely, it’s painful observing a teacher who is on “rote mode” or “winging it mode”.

Lesson plans are for admin. Scripts are for pros. I remember showing a brief lesson plan to a principal but then showing her pages of script that I had written in support of the plan. She said she had never seen that kind of preparation before. I told her the Seinfeld story and she “got it”.

My mother had an old note pad. On the top of each page was the phrase, “Don’t say it. Write it.”

When in doubt, edit.

Let the guy who created the show about nothing remind us that EVERYTHING can get better . . . with editing.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed