|

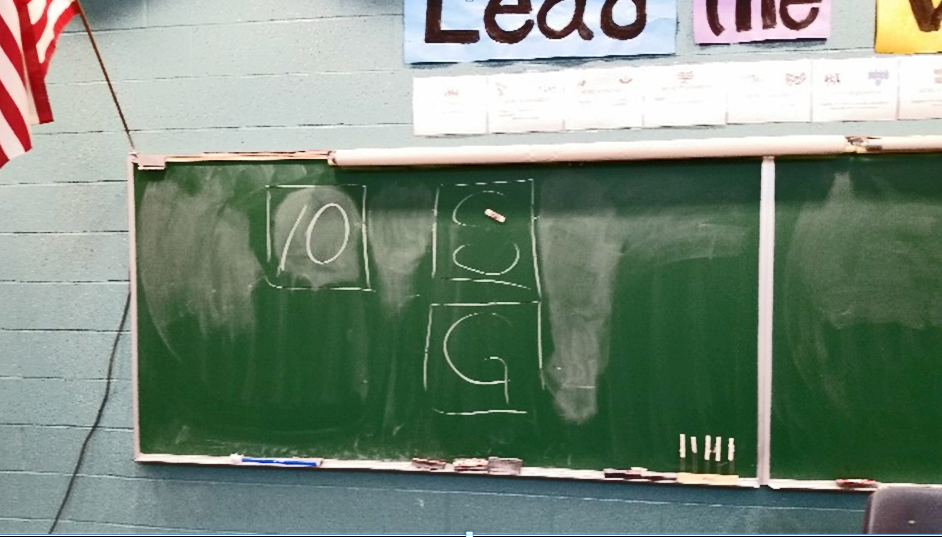

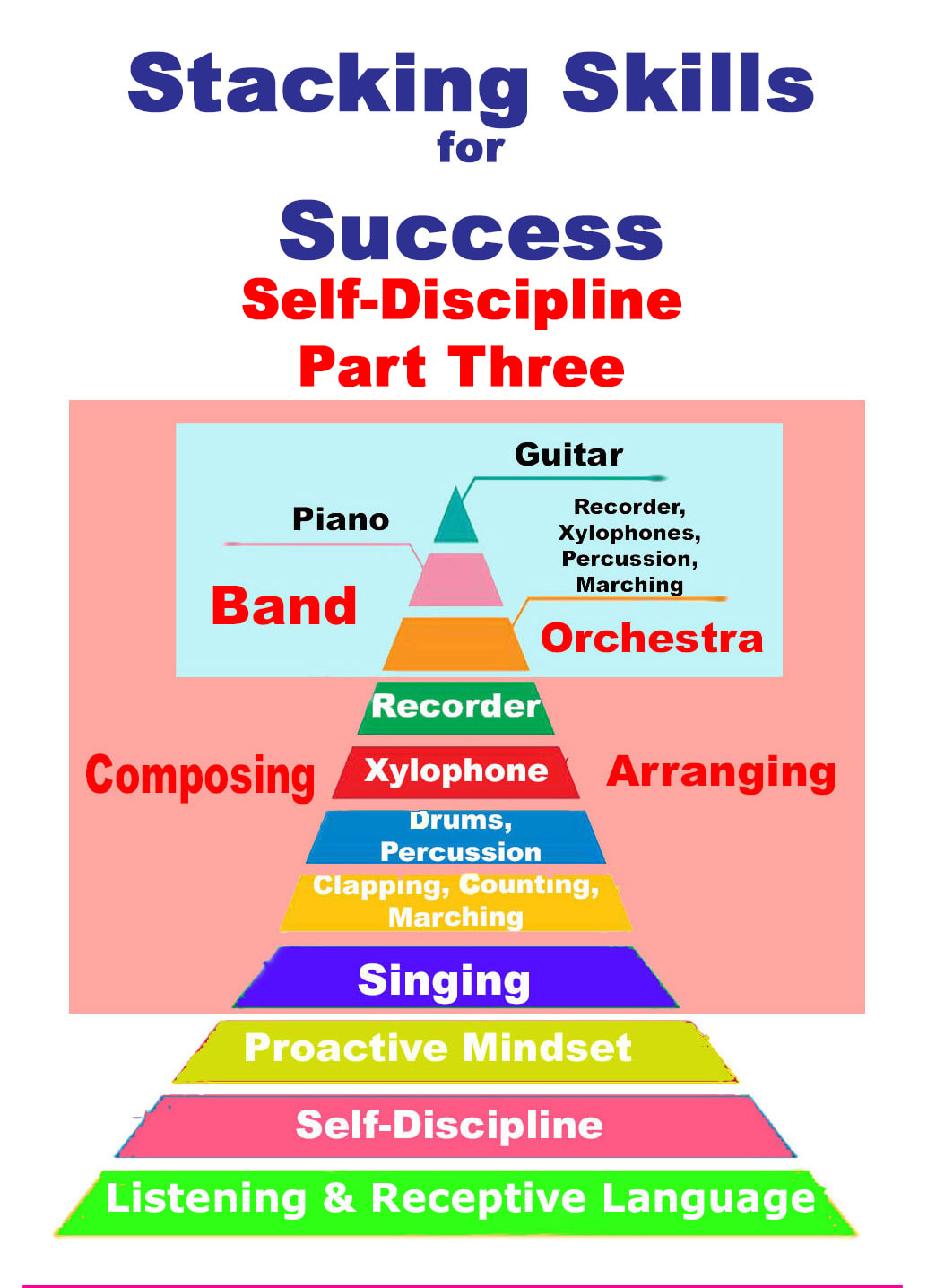

Kids notice which teachers are self-disciplined. They will often ‘play’ undisciplined teachers because they know the reaction will usually be emotional and divert time from studies. Screamers are not disciplined. Don't be a teacher who screams. Use visual imagery to convey your happiness, disappointment, or disapproval. Enhanced self-discipline increases your own work output as well as your student’s productivity. This is especially true with visually communicating to kids when or when not to talk. Before any students ever walked into the music room, there were always two boxes drawn on the chalk board each about a foot wide. One box had an “S” in it and one box had a “G”. Stop and go. There was a magnet in the S as the kids entered the room.

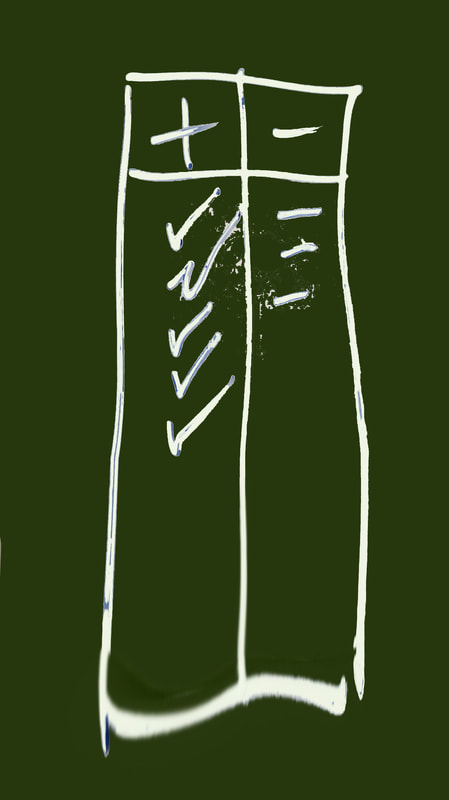

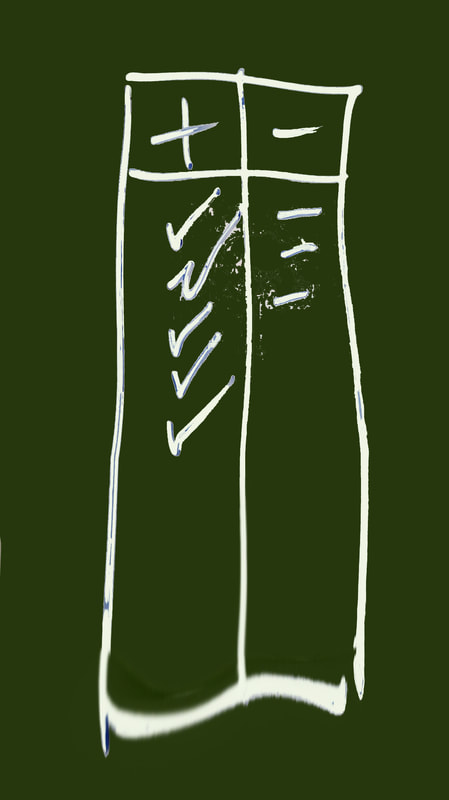

For the rest of their educational life with me, I would never tell them to be quiet or stop talking. The magnet and the pluses and minuses did that. I did not say a word. I saved hundred of hours by not saying "stop talking" that I was able to spend actually teaching, My communication as far as my students' behavior was all delivered visually with only the most minimal aural input. Actually, that's not accurate. When I slammed that magnet on the S, it definitely got their attention from the get-go. If I put the magnet on the S and they immediately got quiet, they got a a check under the plus column. Let me be clear about how often I gave pluses and minuses at the beginning of the school year. It was fast and furious at the beginning of the school year: at least plus/minus feedback every two to three minutes. Whether it was a plus or a minus depended upon what they were doing in that exact moment. The last week of school, I would often share a secret with my fifth grade class kid, the kids I had taught probably the most over the past few years. “Do you know that some of you kids who I've taught for 5 years have never heard me say ‘stop talking’? Not one time. You've never had to hear me whine and complain like other teachers do about being quiet. The magnet always told you, not me. And the “stop” and “go” were never really on the board - they were in your head – and will be there for the rest of your life to remind you when its time to work or to take a break. There is a reason I never told you to be quiet. Musicians never talk to other musicians that way. And that's the way I've always wanted to talk to you, because I knew you were musicians just as I am a musician. From the day I met you I knew you would be a musician and now, as we finish this last class, I know you will continue to be a musician for the rest of your life.” At which point I'd act stuffy and professorial and say something like, “Now go forth, and make music!” We would have a good laugh. Self discipline with kids in the music room also hinges on how they see you, another visual component. If you come in looking professional, you have greater chance of being treated like a professional. If you come in dressed like its Casual Friday, don't be surprised if you get Casual Self-Discipline back from the kids. I was known for wearing a black three-piece suit everyday. I had four of them. The ties changed daily but the suit and vest remain the same. A student once taught me a very crucial lesson. A kid asked why did I always wore my tuxedo to school. Now, of course it wasn't a tuxedo, it was just a three-piece suit. But in his mind, he thought it was the most expensive suit in the world. I used my typical teacher ninja move and turn the question back on the class. “Why do you think I wear my best three-piece suit everyday to school?” One of the kid’s hand shot up. “That's easy - it's because you respect us and you want to show how much you respect us by wearing your most respectable clothes.” I thought long and hard about that kids answer on the way home from work that day and I'm not ashamed to say I got, as Maynard G. Krebs would say, a little misty thinking about the way they perceived our world together. The easiest way to encourage an air of self-discipline, is to actually look self-discipline. Kids notice these things and they make an impression upon them. I'd always chuckle when a kid came to school on Halloween dressed as Mr. Holmes in a suit, tie, and glasses. Another thing that I learned was because kids are much closer to my shoes than they are to my face, my shoes got a lot more compliments. “I really like your shoes Mister Holmes, they're so shiny!” “Well, Becky, I, along with my Rockport dress blacks, would like to thank you for that compliment.” A few final thoughts about discipline and self-discipline in “Stacking Skills for Successes: Self-Discipline - Part 5” As I mentioned in the last post, the visual is the key component for reinforcing ideas of self-discipline. There are seven distinct examples of where I took advantage of visual opportunities to accelerate a student understanding of self-discipline in our room. People see much more than they hear so I didn’t say anything when I observed something I liked during a class. I put a check under the plus sign on my chalkboard. (visual 1) I said to the children in their first class, “You're smart. I don't need to tell you why I put that plus up there. You know you what happened that was good that got my attention.” Conversely, when I saw things that I didn't like, I would put a minus and rarely say anything else. (visual 2) Sure, I would glare and I might put my hands on my hips and be silent for a few seconds, and try and give them that look of shame, (visual 3) but as far as laying into them and giving them ninety seconds of berating language, I didn't roll that way. At the end of any teacher’s screed, there's a moment where everyone in the room is disheartened. Students, especially the ones that didn't partake in any negative behaviors, are ticked off. The teacher, if they're worth anything, will feel shame for having a spewed language that probably wasn't necessary. If the class had no clue why they received the plus or minus, I would tell them the source of my feedback. I found that if I saw the pace of positive things accelerate, I put checks up I put check up at a corresponding rate. (visual 4) When this happened, kids responded . . . . , you guessed it, positively. At the end of class, the balance sheet would be rectified like a check book (visual 5) with the negatives deducted from the positives, because one thing every child needs to learn is nothing is free. For every minus I erased, I also erased a plus. (visual 6) As the kids said, “The good ones pay to get rid of the bad ones”. If the process started out with more pluses than minuses, the reality of squandering our profits was reinforced. If we ended the class with more minuses than pluses, that resulted with a net lose. As Ernest Lawrence Thayer said, “There was no joy in Mudville” on days like that when their teacher came to pick them up. There would often be no “So Long” song, no “Rotten Pumpkin Potpourri” room spray as they left the room, and worst of all, no smiles as they silently left the room. I would tell the classroom teacher of their poor choices and ask the kids what they did differently than they did on a day when they earned ten pluses. I would write down what they said and visually post those better choices on the chalk board before their next class began as a reminder. (visual 7) Our bad choices will often penalize our good intentions and we have to learn that with the fewer bad choices we make, we will have more good things at the end of the day. The amount of positives that classes earned would often be the subject for conversation as we were getting ready to leave class. “Wow, you guys did even better than Ms. Smith's class. They only had twelve pluses. You had seventeen!” Or “I can't wait to tell your teacher how well you did today and how many pluses you got. And whatever you do, don't tell her about the minuses. You paid them off with your pluses so those minuses don't exist anymore. They're just between you and me. She'll only know that you got seventeen pluses today.” This tact also gave momentum to self-discipline: “Maybe we won't get those five minuses tomorrow and we'll walk out of here with a . . . .” and then I would pause and some kid would yell “Twenty-two!”

“Yeah, wouldn't that be cool, to get 22 pluses?” In my next post, I'll describe a foolproof system for helping your kids know when to talk and when to be quiet. That'll be in “Stacking Successes: Self-Discipline - Part 4.” Before we go much further, let's find out just how self-discipline we are. This assessment is very unscientific but it'll give some good, fast, and dirty data as to where to begin ourselves in having a cogent self-discipline program in our own lives. Do we finish projects that we start? Do we avoid setting goals because we know we're simply not going to reach them? Do we find satisfaction in postponing fun activities until we accomplish what needs to be done in the moment? What are examples of short as we’ll as long term delayed gratification in our personal and professional lives? Is “close enough” good enough? If we haven’t established patterns and habits of self-discipline, how do we expect to pass it on to our students? As I like to say, “Beware the naked man who offers you the shirt off his back”. Back to the power of visuals when teaching self-discipline. As you’ve come to see from Part One, a lot of the underpinning for my philosophy on discipline and self-discipline in the classroom rests on visual images, so let's start with one right now. How would you describe the image of a self-discipline music class in an elementary school? Let me give you a few of my descriptors. Children quietly enter the room with no initial prompts from the teacher. The children sit in an orderly fashion, not talking or touching one another, attention focused on the teacher, student, or object of the moment. The teacher is not yelling, but using a well-modulated voice. The teacher is maintaining eye contact at all times with the class. There are visuals on the chalkboard or display area that visually reinforced the positive feedback the teacher is constantly feeding the class. While the teacher might not always be smiling, the class usually is. The children are allowed short breaks and when given one prompt from the teacher, promptly resume activities after the break. The class ends in an orderly fashion with constructive feedback from the teacher detailing just how well the class did that day. Notice that I did not include any specific activities other than an opening and a closing. When students walk through your classroom door for the fist time, the first thing students will determine is what you are about. As my father used to say, people don’t rely on their first impressions; people usually wait about 6 seconds before they size you up. There is no time like the first class to start developing good self-discipline habits in your class. How you come across in those first few minutes is crucial for setting the tone for self-discipline as well as discipline. So how do you insure that the second that kids walk through your doorway, they will be responding in the positive way you anticipate? You cheat. You meet them in the hallway as they come approach your room with their teacher. The following plan is designed to kick-start self-discipline and establish norms with your students. As they queue up outside your door, you give a no nonsense sixty-second statement of what you expect as they walk through that door. Your words have to be delivered in a no-ifs-ands-or-butts tone. This is typically what I said: “Good morning. The line leader will patiently wait and listen for music to start playing inside the room. Once the leader hears the sound of music, they will lead the class into the room at which point, everyone will stay in line, not move around to your friend, but stay in line, and sit down in rows. When one row fills up, the next person starts the next row. We will remain silent until after the song is finished playing.” I would then go into the room, start the music and stand by the door and make visual eye contact with each child as they walk through the door. As the children came into Bach’s “Well-Temple Clavier Book 1 Prelude 1”, I would not smile, I would not grimace; I wore the countenance of the Sphinx, a look that says I'm silently looking at YOU and taking all of this in. If there were any SNAFUS with formation of lines sitting on the floor or in chairs, I would quietly assist. If someone try to engage me in conversation, I will put my index finger up to my purse lips and shake my head “no”. After all the children proceeded, I might look for a child who is seated the most upright manner or maybe a student who is sitting with their hands folded in their lap and quietly walk up and give them a guitar pick. I might also put a positive check under the plus sign on my chalkboard. “Pluses and Minuses” are given throughout the class. The very first few positives are given to kids who stand out as exemplary role models.

As Bach’s music played, I would primarily stand at the front of the class, between them and my piano. If needed, I would walk in between the rows of children just to look at them and know let them know that I am observing them. If a child decided to test the boundaries and talk, I would immediately walk up to that child, lean over, put my index finger up to my lips give a stern look, and shake my head “no”. No audio response from me, just visual. Why do I do these things? Because these things worked for me and my classes. Because this is a pattern of behaviors that I will do at the beginning of every single class that I ever teach these children. Every. Single. Class. I will not waver from this pattern. I will give them one of the greatest gifts that a teacher possesses: the gift of them being able to predict with 100% accuracy how I'm going to behave and what I'm going to expect from them every single class. Often, after Bach concluded, I sternly looked at the class and said, “Look how excellent you appear. Observe how intelligent you sound.” “But, Mr Holmes, we're not saying anything, we're just being quiet.” “Exactly. Silence is often the greatest evidence of someone’s intelligence!” More on the connection between the visual and soft discipline in the next post “Stacking Skills: Discipline and Self-discipline - Part Three” |

AuthorBoyd Holmes, the Writer Archives

June 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed