When I was seven, my father started teaching me how to play pool.

He worked at WILM-AM, a radio station that was on the first floor of the International Order of Odd Fellows building at Tenth and King Street in Wilmington.

The second floor was another radio station, WDEL-AM.

The third floor was reserved for the Odd Fellows Club.

It was like rolling time back by a hundred years.

The old-style accordion elevator doors opened to a cavernous hall full of echos, rarely populated by members, dimly lit with six pool tables, a couple of poker tables, and an old fashioned carved wooden bar complete with spittoons and a jaded bartender.

My father’s cigarette smoke drifted and hung in the air just above the wood bead score wire in it’s own little mesosphere.

It might have been just a pool hall but when I was there with my dad, it felt like sanctum sanctorum.

One of the first things my father forced me to do as I was learning the mechanics of the game was to play position pool and always call my shot. That meant that I had to read the table, assess the best pocket for each ball given the current location of the cue ball, and plan where my next three shots were going.

In many ways, when teaching music, I approached my year-long planning that way, like a game of position pool. I wanted to have skills and ideas lined up that led from one to the next.

I called it stacking.

Why?

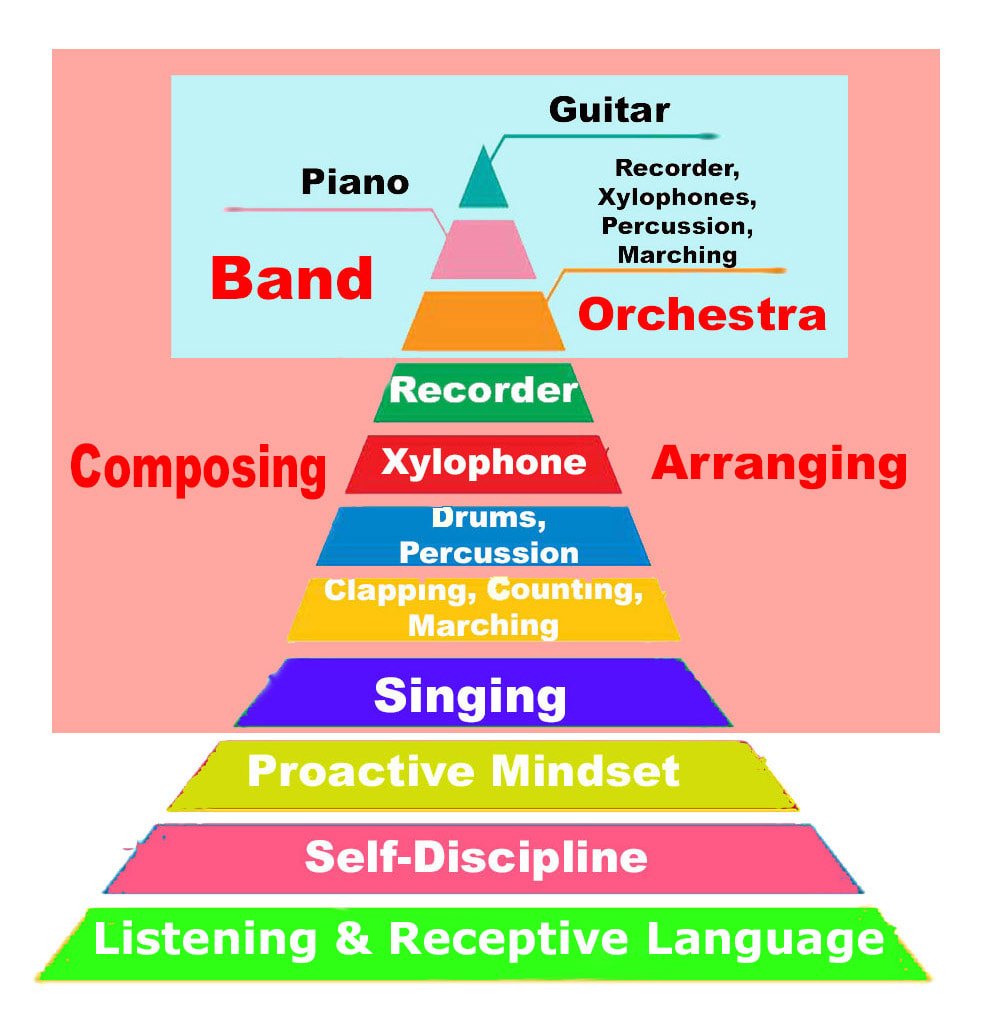

Because each new skill or activity was stacked on top of the preceding attained skill or activity.

Stacking give you more bang for your buck.

Just like two speakers achieve more power when coupled directly next to each other rather than spread far apart, musical concepts gain more power and momentum when coupled.

Stacking also reduces a student’s anxiety level because they are always referencing previously attained skill when attempting new ones.

This diagram gives you a basic idea of how I coupled basic concepts in music.

He worked at WILM-AM, a radio station that was on the first floor of the International Order of Odd Fellows building at Tenth and King Street in Wilmington.

The second floor was another radio station, WDEL-AM.

The third floor was reserved for the Odd Fellows Club.

It was like rolling time back by a hundred years.

The old-style accordion elevator doors opened to a cavernous hall full of echos, rarely populated by members, dimly lit with six pool tables, a couple of poker tables, and an old fashioned carved wooden bar complete with spittoons and a jaded bartender.

My father’s cigarette smoke drifted and hung in the air just above the wood bead score wire in it’s own little mesosphere.

It might have been just a pool hall but when I was there with my dad, it felt like sanctum sanctorum.

One of the first things my father forced me to do as I was learning the mechanics of the game was to play position pool and always call my shot. That meant that I had to read the table, assess the best pocket for each ball given the current location of the cue ball, and plan where my next three shots were going.

In many ways, when teaching music, I approached my year-long planning that way, like a game of position pool. I wanted to have skills and ideas lined up that led from one to the next.

I called it stacking.

Why?

Because each new skill or activity was stacked on top of the preceding attained skill or activity.

Stacking give you more bang for your buck.

Just like two speakers achieve more power when coupled directly next to each other rather than spread far apart, musical concepts gain more power and momentum when coupled.

Stacking also reduces a student’s anxiety level because they are always referencing previously attained skill when attempting new ones.

This diagram gives you a basic idea of how I coupled basic concepts in music.

Yes, Dorothy, all roads lead to guitar.

But it’s the journey, not the destination, right?

Planning this way allowed me to predict with ninty percent accuracy before the year started what we would be doing in my music room the last two weeks of the school year.

It’s all about the architecture, the infrastructure, and the meat that you put on the bones.

Over the years, I learned that my best years resembled good stories : Introduction, exposition, development, recapitulation, plot twist, resolution, and coda.

I orchestrated my planning so that the last forty-five minutes of the school year that I spent with my students resembled a grand dénouement where we connected all the dots like they were some magnificent constellation in a spring night sky.

So yes, it all started with my father making me read the table, call my shot, and then make it.

Know where you’re going in your school year.

Decide how you can stack the skills and material you are going to present over the next nine months.

Know your shot and call it.

But it’s the journey, not the destination, right?

Planning this way allowed me to predict with ninty percent accuracy before the year started what we would be doing in my music room the last two weeks of the school year.

It’s all about the architecture, the infrastructure, and the meat that you put on the bones.

Over the years, I learned that my best years resembled good stories : Introduction, exposition, development, recapitulation, plot twist, resolution, and coda.

I orchestrated my planning so that the last forty-five minutes of the school year that I spent with my students resembled a grand dénouement where we connected all the dots like they were some magnificent constellation in a spring night sky.

So yes, it all started with my father making me read the table, call my shot, and then make it.

Know where you’re going in your school year.

Decide how you can stack the skills and material you are going to present over the next nine months.

Know your shot and call it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed