|

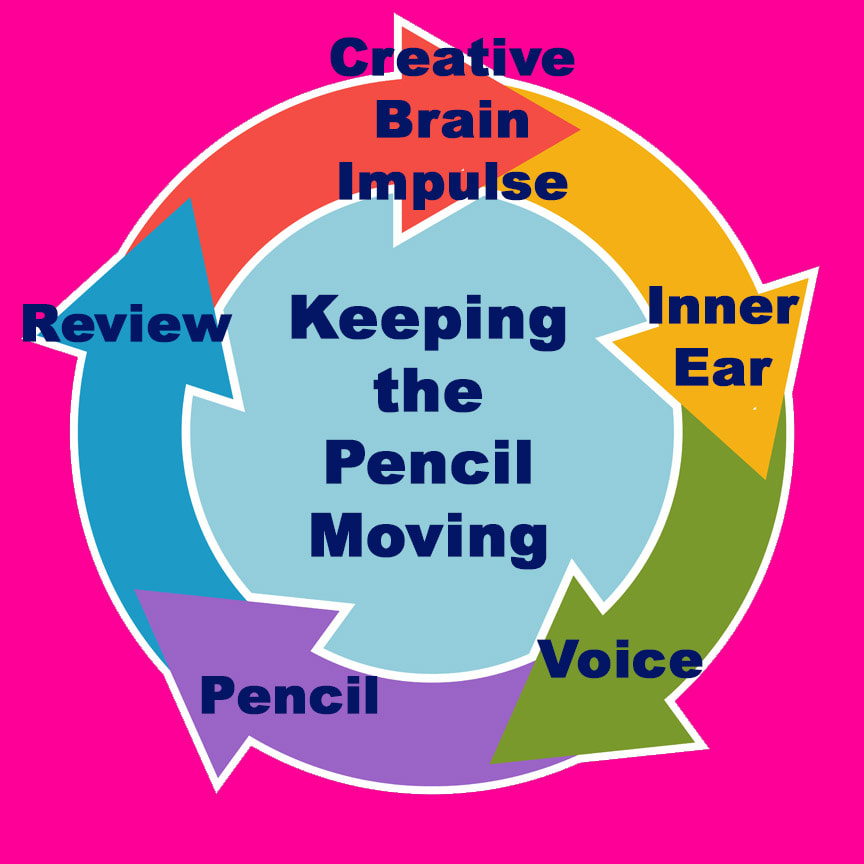

By now, I hope you are seeing that “moving the pencil” is indicative of learning how to audiate both melody and harmony in real time. This diagram is how I think I developed the skill of audiation with a pencil. Each step started like an individual cell of a cartoon that gradually sped up to the point that there were no small isolated steps but rather one continuous movement, a lingua franca to experiencing musical sound. As with much in music, repetition is key in acquiring these skills.

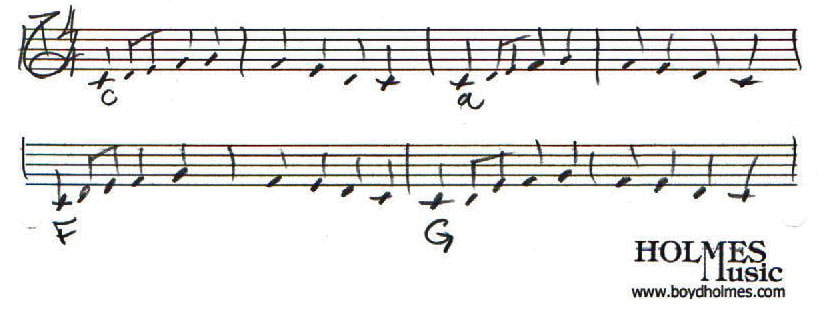

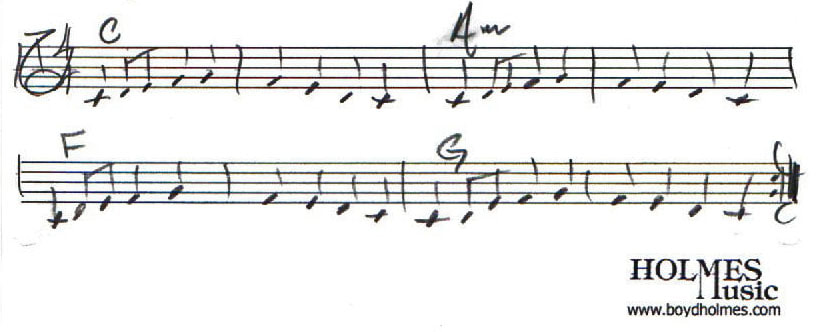

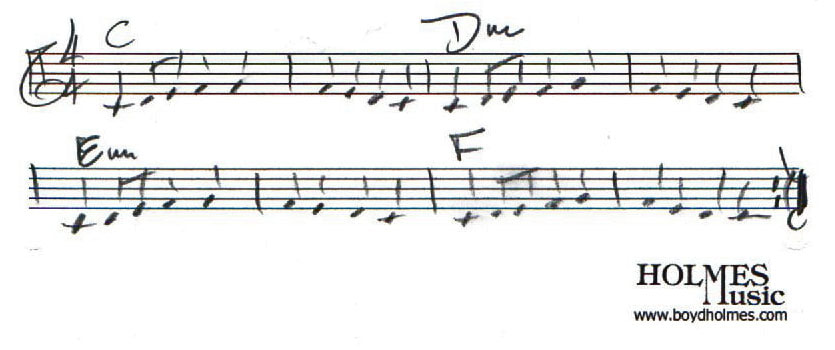

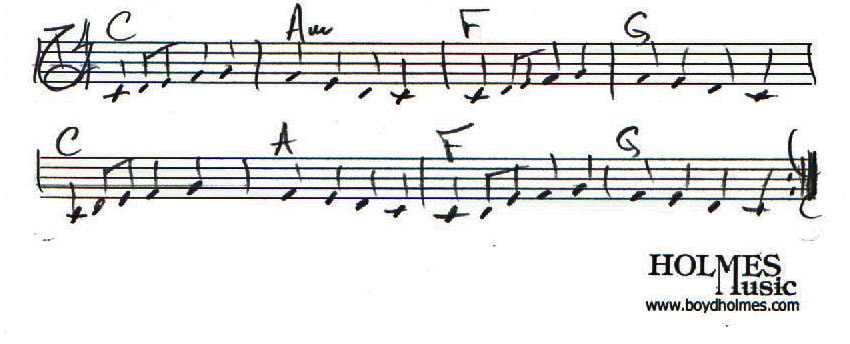

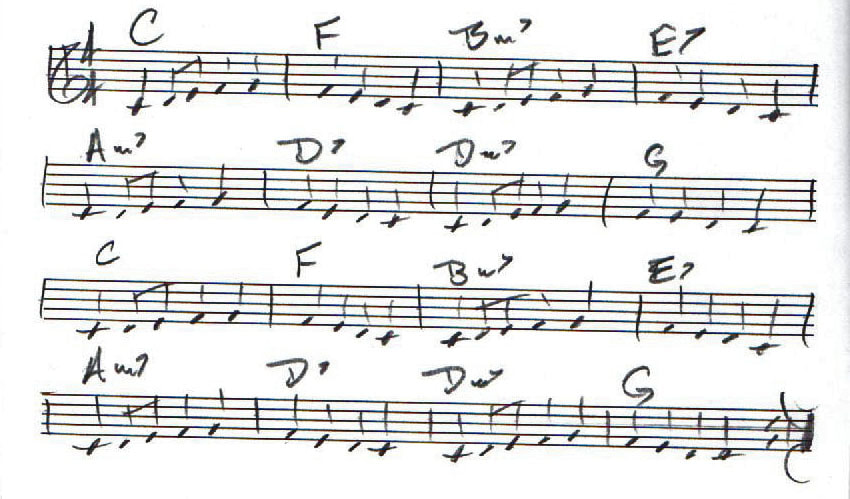

The example we’ve done are all in the key of C major. There are another eleven major keys to become facile in with your pencil – as well as your inner ear. Just as you probably learned how to run basic eighteenth century harmonic progressions in theory classes, those seminal I-IV-V7 sounds are only the beginning of audiation. As it becomes increasingly easier to write melodies when you are steadily feeding new and different melodies to your memory, your vocabulary of harmonies has to grow as well. There are theories that when perfect pitch develops in a young child, one of the greatest influences is continuous exposure to both tonal and atonal melodies and harmonies. Most of us grow up in a society where traditional harmony rules the day. The more you are able to approach those melodic and harmonic concepts as a child in a play-like way of endless experimentation, the more you can experience and embrace "outside" harminies and melodies, the more supple your audiation skills will become. As a first year double bassist, I remember reading a bass column in the jazz magazine Downbeat where the author claimed that he had learn a thousand songs by memory. I couldn’t believe that I would ever have that kind of knowledge or ability. The focus of the article was on common progressions and typical, predictive patterns in melodies. While most of us distinctly remember the particulars of our first kiss or when we learned how to ride a bike, audition skills have a way of creeping up on us. With supple audiation skills and a good memory, a thousand songs isn't an unreasonable possibility. One day you are struggling to “hear” and gradually you realize that everything you hear is a variant of something you’ve heard before . You are able to synthesize your past listening experiences with new creative input. For me, audiation used to be sequential procedures that at first were like a toddler learning how to get around their world: crawl, stand, step, walk, run. We don’t remember our first independent successes at crawling – but our parents do. I saw my teddy bear across the room and suddenly had a deep desire to hold it so I started to crawl. Being prepared for the significant motivation was the key for me crawling as well as audiating: I wanted to do it because it gave me pleasure. I wanted it and was willing to make sustained efforts to achieve my goal. In college, many of my classmates had to learn how to audiate on command. First and foremost, it was required for a grade. Audiating for me started when I was a toddler when everything was a new experience and my world grew exponentially because of my developmental curiosity. Just like a lot of early childhood, audiation was messy, not always a straight line of success or growth, lacked a vocabulary, but ultimately fulfilling. By the time I got to college, I was spending hours pounding on a practice room piano, exploring more complex and textured melodies and harmonies. They stayed with me after I left the practice room. If you are working to develop your audiating skills, the best advice I can give you is that maybe you might want to “play” instead of “work’. As my friend Jack Jadach would say, “call off the dogs” and let the action progress more from a place of experimentation and play. That’s not to say that as an adult, programing your time to a goal is different than a child at play. At it’s core when I was a child, music and audiation was fun for me – and lucky for me, it still is. Here is a video I made for my recorder students concerning hand position. If you haven’t been following along in part one, two, or three, check them out before progessing. So here’s a little exercise to get the pencil moving. Take one of the songs you previously copied. In each measure, circle the notes that can be found in chord that is over that measure. Scat the song with the chord tones at ff and the non-chord tones at p. Notice how most of the notes in the melody are in the chord. Now, let’s move to the piano and scat the same song as we normally would while we play the letter name of the chord either as half notes, whole notes, or with a slight repetitive rhythm. It’s not just enough to move the pencil while writing a monophonic melody. The melody needs to be grounded to a harmonic progression, just like the melodies in the songs you copied were anchored to a chord progression. It’s time to address the chicken and egg conundrum: what comes first - the melody or the chord progression? The basic is answer is that they occur simultaneously. The melody is structured around chord tones. We’re going to “cook book” our first melody/chord progressions to get our feet wet and our pencil moving. Imagine you need to write a two bar practice etude for a young trumpet student. The trumpeter knows quarter, half, and whole notes as well as the pitches C, D, E, F, and G. If you played an instrument as a young child or took a methods class in college, you probably played an etude in your first book that fell into these parameters. Take your pencil, write your treble clef, 4/4 time signature, and then write those five notes in an ascending line starting on C up to G and directly back down to C. Let’s make them all quarter notes. Make sure you scat them as you write them. Scat with a loud voice! By now, you have probably noticed that nine quarter notes are one beat too many for two bars. There’s an easy fix. With the exception of the very last beat, the low C, make any two consecutive notes of the first seven notes eighth notes. Success! You should have an exact two bar phrase – seven quarter notes and two eighth notes ( I put my two eighth notes on the second beat of the first measure). Ok. Scat it. Do you like it? Let’s try some editing. Think about position the two eighth notes somewhere else in the two bars. Scat it as you write it. Which version do you like best – the first or second? If one sounds a lot better than the other, go with the one you like. If you still think there might be a better place for those eighth notes, keep experimenting by moving the eighth notes while writing and scatting. We’re looking for the version that sounds most natural when we scat it. Found the best two bar version for you? Great! On a new sheet, write out your two bar phrase four times in a row to create an eight bar etude. Scat it as you write. Remember, loud! Next, we are going to write a bass note under the first notes of the first, third, fifth, and seventh measures. The four bass notes will be C, a, F, and G. Give yourself a little four bar C bass ostinato intro before you scat your melody while playing the bass notes. Imagine your trumpet student playing this etude while you give him a neat little bass rhythm on the piano. Groovy! Let’s flesh out those bass notes to full chords; C, a , F, and G. An “A minor chord” is symbolized by a lower case “a”. All lower chase chords will be minor. Write the eight bar melody again but this time, write the chord names over the first notes of the first, third, fifth, and seventh measures. Scat the etude again while you play whole note chords in your right hand with a simple ostinato bass part in your left hand. Change the final single bar line into a repeat sign. This thing will now give “This Is the Song That Never Ends” a run for its money. Play it over and over as you scat the melody. No matter how easy the melody is (and it is very easy), keep reading it as you scat it. Stop – and softly scat the melody while you THINK about the sound of the bass and chords. You won’t necessarily hear the chords in your mind – but I bet you will feel them and get a different sensation as your eye tracks through each note in your head. Now write out your melody with new roots under each successive two bar phrase: instead of C, a, F, and G, let’s use C, D, E, and F. Scat it with these bass notes on the piano. Feels different, right? Instead of a C, Am, F, G progression, we’ll use these bass notes to anchor a new progression: C, d, e, and F. Try all these chord progressions. Slash chords like F/G means play an F major chord over a G bass note. Scat and play the melody and progression loud two times in a row followed by softly scatting it a capella and feeling the harmony as you scat: C, am, F, G Cmaj7, am7, Fmaj7, G7 Cmaj7, am7, Fmaj7, F/G C, dm, em, F Cmaj7, dm7, em7, Fmaj7 am, em, F, E am7,em7, Fmaj7, E7/G# Let’s try accelerating the harmonic rhythm. Instead of two measures for each chord, lets switch chords every measure. Write out our eight bar phrase and double it to sixteen bars with a repeat sign at the end. Scat while you write. Try this eight bar progression with one chord per measure. C, F, b, E, a, D, d, G

Cmaj7, Fmaj7, bm7, E7, am7, D, dm7, F/G C, G/B, Am, G, F, em7, dm7, F/G Let’s use our old pattern of two times with piano nice and loud and then softly while you audiate the harmony. We’ll finish this exercise in “The Songwriter’s Notebook: “Keep Your Pencil Moving” Explained – Part Five” |

AuthorBoyd Holmes, the Writer Archives

June 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed