|

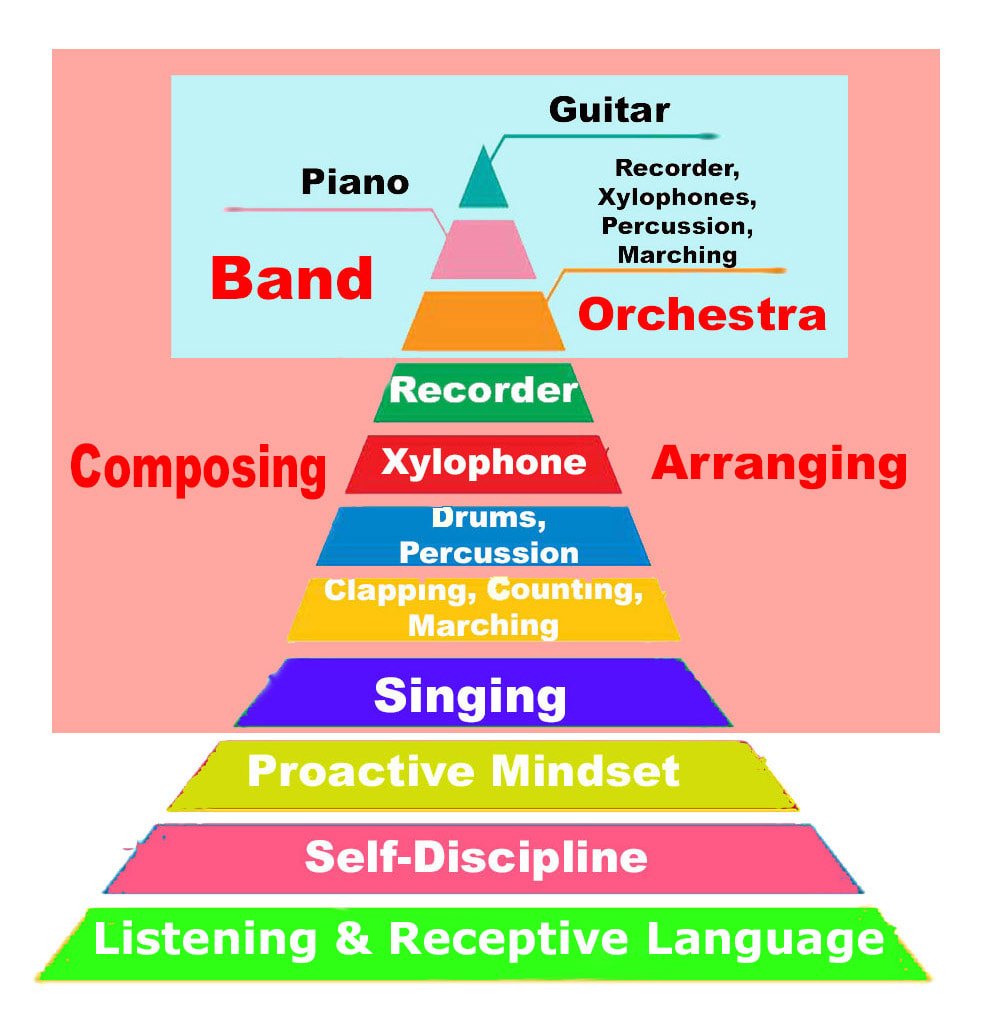

When I was seven, my father started teaching me how to play pool. He worked at WILM-AM, a radio station that was on the first floor of the International Order of Odd Fellows building at Tenth and King Street in Wilmington. The second floor was another radio station, WDEL-AM. The third floor was reserved for the Odd Fellows Club. It was like rolling time back by a hundred years. The old-style accordion elevator doors opened to a cavernous hall full of echos, rarely populated by members, dimly lit with six pool tables, a couple of poker tables, and an old fashioned carved wooden bar complete with spittoons and a jaded bartender. My father’s cigarette smoke drifted and hung in the air just above the wood bead score wire in it’s own little mesosphere. It might have been just a pool hall but when I was there with my dad, it felt like sanctum sanctorum. One of the first things my father forced me to do as I was learning the mechanics of the game was to play position pool and always call my shot. That meant that I had to read the table, assess the best pocket for each ball given the current location of the cue ball, and plan where my next three shots were going. In many ways, when teaching music, I approached my year-long planning that way, like a game of position pool. I wanted to have skills and ideas lined up that led from one to the next. I called it stacking. Why? Because each new skill or activity was stacked on top of the preceding attained skill or activity. Stacking give you more bang for your buck. Just like two speakers achieve more power when coupled directly next to each other rather than spread far apart, musical concepts gain more power and momentum when coupled. Stacking also reduces a student’s anxiety level because they are always referencing previously attained skill when attempting new ones. This diagram gives you a basic idea of how I coupled basic concepts in music. Yes, Dorothy, all roads lead to guitar.

But it’s the journey, not the destination, right? Planning this way allowed me to predict with ninty percent accuracy before the year started what we would be doing in my music room the last two weeks of the school year. It’s all about the architecture, the infrastructure, and the meat that you put on the bones. Over the years, I learned that my best years resembled good stories : Introduction, exposition, development, recapitulation, plot twist, resolution, and coda. I orchestrated my planning so that the last forty-five minutes of the school year that I spent with my students resembled a grand dénouement where we connected all the dots like they were some magnificent constellation in a spring night sky. So yes, it all started with my father making me read the table, call my shot, and then make it. Know where you’re going in your school year. Decide how you can stack the skills and material you are going to present over the next nine months. Know your shot and call it. I was in 6th grade in the middle of a trumpet lesson on a Saturday morning with my teacher, Mike Gibson.

Mike was hip, a combination of master musician, orchestrator, sensei, guru, and role model. Tall, glasses, long hair, mo-ped, boots, corduroy jackets, Marlborros. My weeks centered around the one half-hour that I spent with him. His lessons were no-nonsense. He effortlessly talked music theory. And expected me to hang with his thoughts. He often had me scat my etudes before he allowed me to play them. It seemed that he was the essence of knowing not just about music but how music worked. And I want to be like him. And then there was his brief case packed with hand-written scores and parts, all on ultra-think Pissanto manuscript paper and created with an osmiroid fountain pen that he often brandished during my lesson. I mean, he was one of those confident guys who wrote first editions in ink. Mike could always sense when my embouchure was begging for mercy because my protruding upper teeth were cutting into my lips. We would take a short break, drain the blood from my spit valve, and talk for a minute or two just to allow the juices to flow back into my lips. During those interludes, we discussed a wide range of topics: books, silent films, the Renaissance, jazz, instruments, Russia, arranging, music, art, sports. Even more importantly, he wanted to know what I thought. He would actually shut-up, lean in, and critically listen to my point-of-view and weigh my words. After every lesson, I’d always have a name, word, or idea I that he would casually drop in conversation that I was clueless on and needed to ask my parents about or research in the library. But on this one day he was more pensive then talkative. After about ten seconds of silence, he turned and looked at me as if he was going to ask for the secret of the ages. “Sophia Loren . . . . . or . . . . . Gina Lollabrigida?" He looked at me and waited. I did not see that one coming. No one told me that “Italian actresses” was going to be on the test. I paused. I knew who both women were, knew they were beautiful, had seen their pictures in Life and Time magazine many times, and knew they had their own distinctive perspectives, especially in the articles I had read and roles they had played. Was he asking me about their films, their looks, their accents? Or maybe . . . maybe he was asking something more elemental about their essential aura? I slowly answered in that tone of voice a student uses when they're not sure if the answer they're going to give is correct. “Gina Lollobrigida . . . ?” His face lit up. “Yeah, of course, Gina Lollobrigida! I mean no comparison, right?!" He lit up another Marlborro. "Ok, back to the horn.” And that was that. We didn't talk about it again. But his smile seemed more knowing. Had stock had risen in his eyes because of my answer? It seemed so. I was left with my own personal notable question which was what if I'd said “Sophia Loren”? I had a feeling he would have made it work. So why have I done this?

Several reasons. For non-musicians, these “rules” give a glimpse into what goes into a musician’s preparation and thinking on a gig. As far as musicians go, I’ve collected these “rules” primarily for today’s younger players who are starting out with their own “gigging life” and want to be more “street-smart” about the process of gigging. When my generation was first going out to gig, many of us were in our early teens. There were more opportunities for “cross-pollination” among musicians of different ages and calibers than there is today. Each of my first gigs seemed like a “how-to’”, a “what-not-to-do”, or a “master class” experience in gigging. Musicians like Hal Schiff, Lloyd Johnston, Tim Laushey, John Spragg, Al Smith, Vinnie Marinelli, Jim Daley, Frank Germin, Jack Malloy, Warren Keizer, Joe Laird, Russ Williams, Al Santoro, and Paul Richardson gave me a shot when I was just starting out, some of them hiring me when I was still in high school, and I owe them more than I can say. Then there were guys a just few years older than me like Pete BarenBregge and Larry Spenser who were great mentors and role models. These “rules” aren’t meant to be edicts to restrict having fun doing what you do. In fact, many musicians already exhibit these behaviors not because they are “rules” but because they have become deeply rooted habits and lead to successful gigs. One musician’s oppressive rule is another musician’s ingrained good habit. These suggestions are offered to free you from having to think about the efficacy of what you are about to do in any given gigging situation. You want to do as little thinking as possible on a gig and relying on instinct and good gigging habits. Moreover, all these recommendations help you effectively communicate and engage your listeners. While they can lead to financial dividends, ultimately these guidelines will remind you that the gratitude you want from your audience is dependent on the choices you make in real time on a gig. You will be appreciated more than you can imagine as a musician once you start being appreciative of all that others have done for you. The “Rules” Gig Rule #1: The client is always right – in real time. Gig Rule #2: Gently smile – not grin - at all times. Gig Rule #3: You were hired to play music – not to be funny, tell stories, teach, or be therapeutic. Gig Rule #4: Have a set list with more songs prepared than you will need. Gig Rule #5: Get the venue’s wifi password and log on before you start to play so you can look up a requested song’s lyrics on the fly. Gig Rule #6: If you have never played the venue before, bring extra extension cords as well as a few ground lifts in case of sixty-cycle hum issues. Gig Rule #7: Pack an emergency bag with extra strings, extra bridge pins, an extra XLR cord, nine volt batteries, and _______________. Gig Rule #8: Start on time and play an extra song at the end. Gig Rule #9: Before you finish a song, know what the next song will be and start it as quickly as possible. Gig Rule #10: The only person you are allowed to make a joke about when the mic is live is yourself. Anything else is an unnecessary risk. Gig Rule #11: Don’t swear. Imagine that everyone in front of you has the morals of a born-again Christian. Gig Rule #12: Find out what songs people what to hear and then play them. Gig Rule #13: Make eye contact with the audience at least every ten seconds. Gig Rule #14: Understand and perform to the lowest common denominator in the room and only deviate when fulfilling requests. Gig Rule #15: Solicit requests on a face-to-face basis and then play them. Gig Rule #16: If you have to announce any kind of information, write everything out - including phonetic spellings of tricky names. Gig Rule #17: People hear what they see so give them both: something to hear as well as see. Don’t be a statue. Occasionally attract the customers’ attention by moving. Gig Rule #18: Take the fewest amount of breaks as possible. Gig Rule #19: It is better to be not loud enough than to be too loud. Gig Rule #20: Don’t let customers sit in, sing, or play. Gig Rule #21: Don’t perform at a static volume. Always be looking for ways to give variety to your playing and singing and change it up at least every four bars. Gig Rule #22: Even if food is promised, don’t expect to eat. Gig Rule #23: When the set or gig is over, don’t linger: get off the stand quickly. Gig Rule #24: Leave business cards everywhere. Gig Rule #25: Thank someone. And by the way, thanks for reading this. These are guidelines that I developed over the decades. Will every rule apply to you? Probably not, especially if you are opening for Elton at the Beacon. But for most basic gigs, these precepts tend to make the night go smoother than bumpier.

The first twenty were: Gig Rule #1: The client is always right – in real time. Gig Rule #2: Gently smile – not grin - at all times. Gig Rule #3: You were hired to play music – not to be funny, tell stories, teach, or be therapeutic. Gig Rule #4: Have a set list with more songs prepared than you will need. Gig Rule #5: Get the venue’s wifi password and log on before you start to play so you can look up a requested song’s lyrics on the fly. Gig Rule #6: If you have never played the venue before, bring extra extension cords as well as a few ground lifts in case of sixty-cycle hum issues. Gig Rule #7: Pack an emergency bag with extra strings, extra bridge pins, an extra XLR cord, nine volt batteries, and _______________. Gig Rule #8: Start on time and play an extra song at the end. Gig Rule #9: Before you finish a song, know what the next song will be and start it as quickly as possible. Gig Rule #10: The only person you are allowed to make a joke about when the mic is live is yourself. Anything else is an unnecessary risk. Gig Rule #11: Don’t swear. Imagine that everyone in front of you has the morals of a born-again Christian. Gig Rule #12: Find out what songs people what to hear and then play them. Gig Rule #13: Make eye contact with the audience at least every ten seconds. Gig Rule #14: Understand and perform to the lowest common denominator in the room and only deviate when fulfilling requests. Gig Rule #15: Solicit requests on a face-to-face basis and then play them. Gig Rule #16: If you have to announce any kind of information, write everything out - including phonetic spellings of tricky names. Gig Rule#17: People hear what they see so give them both: something to hear as well as see. Don’t be a statue. Occasionally attract the customers’ attention by moving. Gig Rule #18: Take the fewest amount of breaks as possible. Gig Rule #19: It is better to be not loud enough than to be too loud. Gig Rule #20: Don’t let customers sit in, sing, or play. The final five starting with #21: Gig Rule #21: Don’t perform at a static volume. Always be looking for ways to give variety to your playing and singing and change it up at least every four bars. It’s easy to become stagnant over a three or more hour gig. Constantly be mixing up tempos and volumes and everything else in your quiver of skills that showcase your sense of variety. Gig Rule #22: Even if food is promised, don’t expect to eat. Just be happy if you do eat. There is an old story about Miles with his quartet after a gig. All the guys in the band were gorging themselves around a sandwich and appetizer table while Miles was standing away from them. When asked why he wasn’t eating, Miles croaked, “I didn’t come here to eat”. As far as drinking alcohol, with the exception of soda or coffee, expect to pay for every drink you order. If you’re working at a private party or a country club, odds are you shouldn’t drink. Even if you are friends with the client who hires you to play at a country club, the clubs general manager or beverage manger will be rankled if they watch you, ostensibly an employee, drink on the job while they can’t. They really don’t like watching you smile as you cut into their profits because you are drinking for free. If you are playing in a bar, their whole financial model is based on alcohol so management is much more lenient and accepting of musicians drinking while they play. If possible, wait until after the gig to drink. If someone appreciatively buys you a drink during the gig, by all means, bottoms up. If you have a travel mug and feel like putting a beer in it so it gives the impression that you are drinking coffee, go ahead. But if you drink during a gig, know your limits and always stop drinking sooner than later. Don’t advertise that you’re drinking. You’re not Dean Martin. Drinking shouldn’t be a part of your “act”. Tip: if you drink while you perform, it is crucial that you record yourself on the gig so the day after you can analyze if the alcohol had any negative impact on your performance. If it did, cut out the drinking until after the gig. Gig Rule #23: When the set or gig is over, don’t linger: get off the stand quickly. In every venue, you are creating the illusion of a stage, proscenium, and audience space. You won’t have a curtain to open or close so the best way to visually communicate that the music its over is to swiftly get off the stand. Gig Rule #24: Leave business cards everywhere. You’re in business, aren’t you? Gig Rule #25: Thank someone. The server who got you a soda, the couple that requested the first dance song from their wedding, the lady at the bar who turned her head and clapped after a lot of your songs, the guy who was a fan of “Earth, Wind, and Fire” songs, the person who hired you, the table of locals or former co-workers who follow you on line and made a point of coming out to hear you a second or third time – thank all of them. And if there are little kids in the house, I always make a point of going to their table, smiling, taking a knee, looking at them eye-to-eye, thanking them for listening to me, and giving them a personalized guitar pick to remember the occasion. Next up; a summery of the "rules". |

AuthorBoyd Holmes, the Writer Archives

June 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed