|

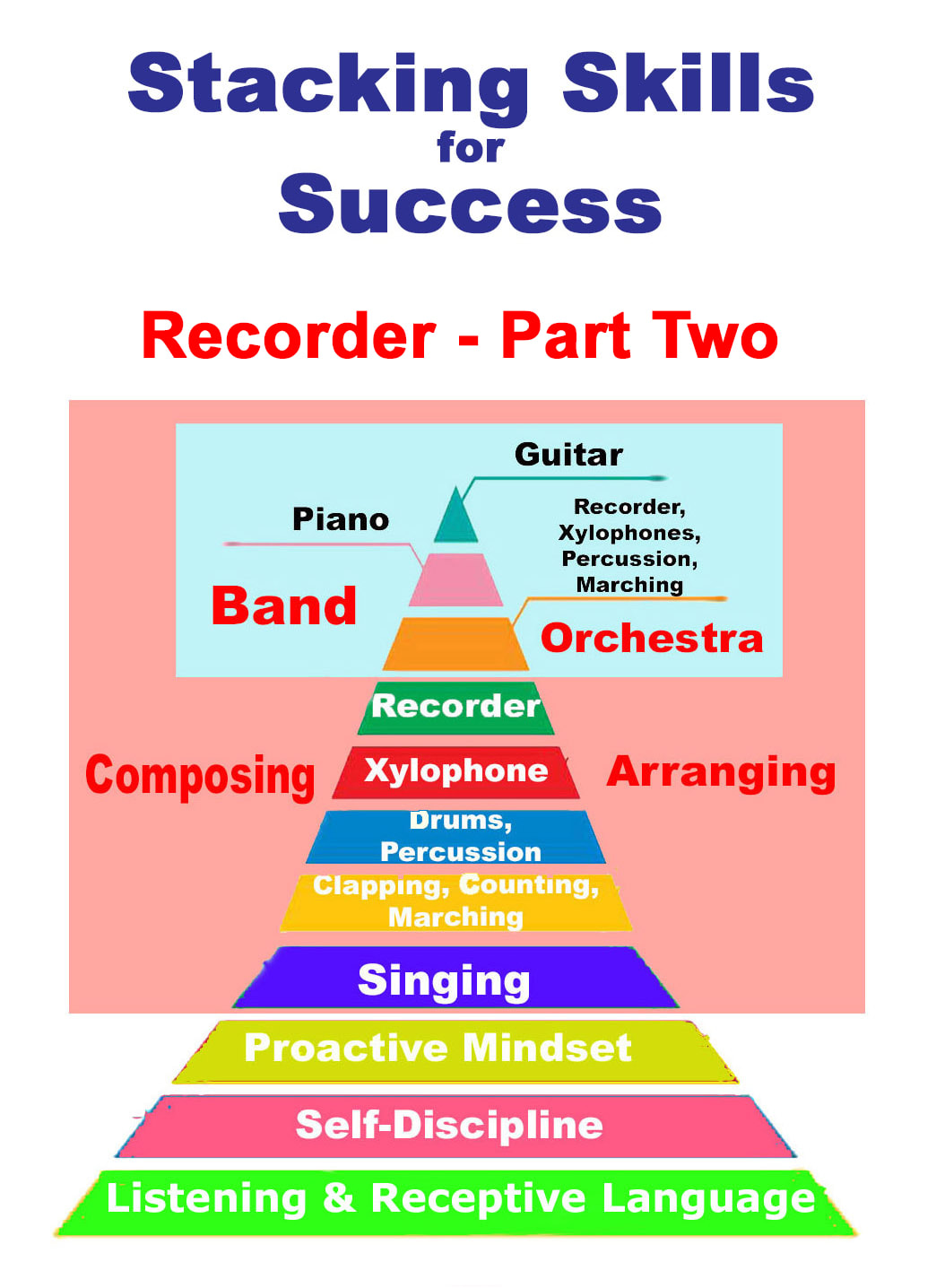

As we’ve been ascending the pyramid of success, each of the skills has been built on the previous skill and, in turn, used as a foundation for the next skill.

Last up was recorder. Makes sense. Check the box for all that fine motor skill development required for recorder as a prelude to band and orchestra instruments. But before we get into it, let's just start with a few questions. Why do 99% of all band and orchestra players quit by the end of their high school or college years? It seems like a hell of a lot of effort, time, money, and sacrifice for something that evaporates at the end of senior year. If playing a band/orchestra instrument is so critical to the musical development of children, why do public schools not provide instruments to all children? Why do the children of families who can't afford an instrument not participate in the band or orchestra programs? When we teach anything in a school, are we teaching for the moment, for the week, for the year? Is the idea to teach for an arc of twelve years so that when students leave a school district, they have achieved a proficiency in a number of disciplines? Are we just filling time? Or is it that at the end of twelve years, we have prepared students to take the knowledge they've gained and richly apply it for the rest of their lives? Why do so many performing groups seem focused on being an arm of the school PR (public relations) machine? And how did music change from child-centered elementary education into competitive organizations, All-state _____________, battling for trophies awarded on clean spats, straight lines on a football field, or adjudicated vowel sounds? It would be convenient to say that society has changed and morphed our view of the Arts. As far as participation with band or orchestra instruments post graduation, an argument can be made that the internet has cut into the aspirations, proclivities, and inclinations of young adults specific to their after-work-hour activities, but it's always been this way. There is a long history of few opportunities in the community for adults to continue playing band instruments or orchestra instruments. Once school was over, the instrument goes in the closet or attic, waiting for the next generation of fourth graders. The mature solo musician had few ways to recreate the band/orchestra experience until the technology of the 1950s started to wake up. There was an interesting development in the 50s called “Music Minus One” after they leave school. These were LP records that were designed for the aspiring amateur home singer or instrumentalist. The LPs had ensembles providing the song accompaniments while the purchaser sang/played the melody. Think of it as archaic karaoke minus the bar, video screen, and inebriated singers. These records came with lead sheets forall the songs on the record in all the functional keys, namely C, Eb, or Bb. The repertoire was as divers as Show tune to classics, Rodgers and Hart to Mozart. My dad a few of these. You could rent some time in local recording studio, cue up your record, and make a recording of you singing along with Nelson Riddle arrangements. In many ways, this was a precursor to the Jamey Aebersold series. These days, we have the ability of digital recording at home. There is the internet, as well as a You Tube karaoke version of almost every song known to man on You Tube, and with today’s technology, the ability to create 44.1hZ MP3 files of a dizzying level of audio clarity that was undreamt of several decades ago. People are using this technology but sadly, not with band or orchestra instruments. The prima facia evidence says that band and orchestra instruments are introduced to elementary students primarily for the moment, for the 12-year program, and once that arc is completed, the instrument experience is over, too. As an elementary general music teacher, I incorporated starting band instruments in as many activities as I could within my classroom. Trumpets with xylophones. Flutes with recorders. I didn't observe that kind of multi-angled approach with most middle or high school music teachers. With the exception of pit bands, school band or orchestra instruments were specifically designed to be played in band and orchestra, not in any other musical class. One of the effects of this mindset is that high school band programs tend to generate potential music educators who’s “be al/end all” all is band, be it marching band or concert band. The individual serves the organization. The organization serves the school. Who serves the individual? This creates a self-perpetuating franchise of band-centric music educators. It is a food chain that only sustains musical life past high school or college if you go into the profession of music education. And even then, it doesn't mean that that music educator is a practicing musician anymore outside of school hours. They often ditch the instrument for the power and glory of the baton. The goal becomes to create music for the twelve year arc of music education. I have a problem with that paradigm. I taught at the elementary level with a focus on an arc spanning the student’s life - not a finite period of a few years within a school district. Luckily, though, there has always been a group of underground matriculating instrumentalists and vocalists who defy that system and buck the norm. Interestingly, these musical rebels originally thrived while still in school, often fling under the music teacher’s radar. I'll be addressing that in the upcoming posts. For now, though, I think the precipitous drop off in band and orchestra instruments post-graduation is worth of discussion and a solution. If you haven’t checked out “Stacking Skills for Success: Recorder – Part One”, read that before reading Part Two. By now, you know that the only thing I enjoy more than teaching recorder is observing kids learn how to practice, problem solve, and succeed on their own with a little help from me. These are life skills that, when generalized, will enhance and improve the way they approach interests and goals for the rest of their lives. Here are a few ideas you might want to try with your recorder groups. First Notes The order in which I teach notes is: B5, A5, G5, F5, E5, D5, C5, C6, D6, F#5, Bb5, C#6 (By the way, I introduced same sequential fingering pattern with flute, clarinet, oboe, and sax.) We spent a HUGE amount of time on BAG. When I introduce F, I simply add the right index finger. There is time down the road to fix the intonation by adding the ring and little finger. First things first with the F: cement the idea of adding single fingers to descend. Piano I accompanied the kids on piano as much as possible. The foundational harmony that piano provided was the perfect safety net. Who is Practicing? Every year, I would order several dozen cheap, colorful, and glittery recorders from the Oriental Trading Company and have them on hand at the beginning of recorder season. By the time the kids knew how to finger the first seven diatonic descending notes, B5 to C5, it was clear who could play this little snippet of music without squeaking or missing a note. Speed was not required, accuracy was. At this early stage, reading those seven notes wasn’t the primary goal; making those seven musical sounds was. It was a lot like playing a musical version of the basketball game named “Horse”. Kids saw it as a challenge and always wanted a shot at playing those seven notes. Everyone got a turn at the end of our music classes to play that seven-note phrase. Typically, the first day I did this, no one would be able to play it. The second time I did it, there would always be at least one or two in each class that could. They were the autodidacts. They were the self-starters. Maybe they were the kids with few toys at home and their recorder was their new favorite. They were the ones that were probably going to be musicians throughout their life to some degree or another. Once a child played those seven notes without squeaking, I would ask, “What’s your favorite color?” “Red!” I would then go into my closet, and come out with a sparkly new red recorder and hand it to them without saying anything. They would typically ask, “Can I play this?” My answer was always, “Not only can you play it, you can keep it, you've earned it. What you just did was very hard and I'm proud of what you achieved. Keep up the great work.” Inevitably the class would spontaneously break into a round of applause. Now everyone wanted to be able to play those seven notes, and I was more than happy to give each of those successful students a sparkly new recorder. Sometimes I would say to our star recorder player, “I have over a dozen guitars at home. You're doing pretty well with that recorder. You might as well start a collection of your own.” Fourth Grade Band If third or fourth grade students had any thought of playing a band instrument the following year, they better show some proclivity to recorder or I wasn't going to recommend to their parents to purchase or rent an instrument for their child. The specter of not playing in band always got the kids attention. “Why would Itell your parents to buy a $300 or $400 instrument if you're not going to be bothered to learn how to play a $3 recorder? I can't in good conscience do that. If you want to play next year in fourth grade, it would be wise to show me that you want to play this year in third grade.” Fourth and fifth grade kids in band loved that I called them a “doubler” – they played two instruments. Their reading and playing skills always reinforced each other on both instruments. Second Grade I was always picking up my recorder to play little songs in all my classes but it was more important for kids to see other kids play. Kids teach kids best. I often arranged time for my recorder players to visit second grade music classes to perform for the younger students. All the instruments we've talked about so far were introduced at the kindergarten level and supported through fifth grade to visiting recorder plyers were always a hit. Recorder was started in third and continued in fourth and fifth grade. I spent a lot of second grade talking up recorder in third grade and how my students had to be ready for the challenge of recorder. That meant they had to be the best musicians they could be with the instruments they had in second grade. Management I made sure that every school I taught in had enough recorders for the grades that were going to be taking lessons. I also built up the idea of purchasing a recorder for $3. I would typically buy them in bulk out of my own pocket at Musician's Friend when they were on sale. I typically bought ivory Lyons recorders for their superior intonation and durability. Don't buy clear or transparent instruments - they easily shatter. Purchase slips went home with kids with a tear off at the bottom. I told kids they should earn the money for their recorders if it all possible. Sometimes I would actually have a checkbox on the return slip notating “My child earned the money for this instrument by doing extra chores”. The collecting of money and getting recorders in the hands of hundreds of students was a major troop movement and felt like something like on the scale of Normandy to me. But it was that “one-to-one” connection, when I looked that kid eye-to-eye, the child handing over twelve hard-earned quarters and me handing them a new recorder, that bonded us on a deeper level. Before we started recorders, I took all of the school-owned recorders home and washed them in my dishwasher. As far as the school-provided recorders, every class had an old copy paper box in my room with the classroom's name prominently on it containing recorders in cases with the kids’ names on it. The box stayed in the music room and were used during music class and recorder lessons. Kids were allowed to bring their personal recorder from home to use in music class. After the opening song, we would always take a short break and that's when I would assign recorder helpers to hand out the recorders to their classmates. Once we went to stop time, everyone was seated and ready to go in front of the Smart Board. Quiet Communication A roomful of recorder is loud. Don’t try to be louder. The best classroom management is quiet management. Use sign language whenever possible. Most of my directions as far as when to play and when not to play were given with hand signals. By now, they knew of “you touch, you take” so they were pretty adept at keeping their recorders flat in their laps. If I put my two hands out, palms down, and gestured downward, that signaled recorders were to be in laps. If I did the opposite, palms up, moving up, that meant recorders were to be in playing position. Making a circle with my left thumb and index finger and putting my right index and middle fingers in the circle meant that recorders needed to be put in their cases. The opposite signal meant take their recorders out. The Foundation: the Bottom of the Pyramid The first three stackable skills are so crucial for student and teacher success on the recorder. This is really where the rubber meets the road as a musician. If kids needed a bit of firm encouragement for practicing at home, I would remind children to be proactive, that while they might be in third grade learning recorder, fourth grade band was right around the corner. Self-discipline allowed them to do the right thing at the right time at home without me looking over their shoulder. I would tell the kids to not just play at home but to listen: listen to their tone because it didn’t matter if they had the correct fingers covering the holes if the tone was ugly. When children came to school with something they learned at home on their own, it was an opportunity when I could look them directly in the eye and tell them this: “You know what? You can put that same effort and thinking into piano or guitar and do just as well. The sky's the limit as far as you’re concerned. You've shown the world that you are a musician when you play recorder as well as you do.” Recorder was the initiation to the idea that we are all responsible for our gains or losses. That’s a heady lesson, one that was painfully reminded to the kids with every squeak they made. I couldn’t fix their problem. All I could do was provide guidance and encouragement. While some kids walked away from the challenge of recorder, some kids learned that solving a problem on their own was a sweeter victory than depending on someone else fixing it for them. It is these life lessons that can make the difference in our music room. For more recorder content, check out my “Recorder Hero” posts from the first ten days of August, 2022. Recorder is, as I like to say, a cookie of a different crumble. When kids learn recorder, they know it is a rite of passage. They are playing an instrument that resembles a band instrument, something “the big kids” play. While children have been reading notation while playing other instruments like xylophone and percussion, for the first time, the kids are playing an instrument where they can't watch their hands as they read notation. This may seem like a small point but it's a huge hurdle for both the teacher and the student. This is also the first wind instrument that a child will play in school. Regulating breath on recorder is a reflection of the old cliché “less is more”. Kids imagine that they have to put a lot of effort into blowing into the instrument. The opposite is true: the effort is always focused on restraint and a solid hand position on the instrument. It is also an adjustment for the general music teacher. This is the intersection of general music and band instructional techniques. I found that with kids reading recorder notation while playing, the strongest solution at first was not individual books or papers but rather using a Smart Board. I supplied music sheets of everything that was on the board with kids who had recorders at home. By the way, note names were never allowed to be written by kids over notes on paper. When dinosaurs still walked the earth and I was a new teacher, I used a chalkboard. If you don't have access to a Smart Board, the best solution is getting your five-line chalk staff maker out and putting quickly drawn etudes on the board for children to read the notes while you point. Back to the Smart Board. Pointing Before the recorders ever came out of the cases, we did a lot of pointing to the board. And saying because “if you can’t say it, you can’t play it”. When I first pointed to the Smart Board for the children to say the pitch names of the notes, I literally had them point with their index finger fingers to the notes as I pointed to them with a stick on the board. It allowed me to focus on their eyes and their hands to see if everyone was following that melodic line. The next step in the progression was to see if they could point with their eyes without their fingers. After they proved adept at pointing with their fingers and naming the note pitches, I explained that they now had to point to each note not with their finger but with their eyes. This is called “eye pointing”. They had to “point” (look) and “track” with their eyes at each note, remembering all the time that “if you can't say it you can't play it”. I called naming the pitches, the rhythms, and the fingerings the “trifecta”. The instrument did not even approach the mouth unless the kids could perform the trifecta; namely, say the names of the pitches of notes in one pass of the etude, the rhythm of the notes in a second pass of the piece, and the fingerings in the third pass. Occasionally, I would have kids do the trifecta silently in their mind while I pointed to the notes.

Just as it's crucial for kids to understand that before a musician makes a sound, they have to think, and that the sound they produce is only the fruition of the thought, it is equally critical for the teacher to do all of this preliminary up-front work to insure the best possible performance with the recorder. I never used those exact words with kids. I said it in different ways. But being able to say it before you play it was the crux of the idea. Then, and only then, were children allowed to pick up the recorder and play as I continued to point to the notes on the board. Some might think that my pointing to the notes a lot at the beginning was a crutch, but I saw it as a reinforcer. It was important for kids to know that at no time were they going to take their eyes off that board, that playing the recorder was going to require a lot of note reading, that they would eventually do the same thing with a piece of paper. Predictions For any of you who are instrumental teachers, one of the highest predictors of success that I've seen with fourth graders with band instruments is a period of time playing recorder prior to learning a band or orchestra instrument. Learning recorder gets a lot of the mechanics out of the way and off the table. Practicing at home, bringing your instrument, saying it before playing it, and general responsibility for your instrument and playing are best learned on a $3.00 recorder than a $400.00 saxophone. If you want a successful band program, make sure your general music teacher is teaching recorder in 3rd 4th and 5th grade. It's one of the greatest reinforcers for band or orchestra that can be provided for children at that age. Up to this point, children have not had an instrument at home that they are learning in school. Recorder is the first one. Assessments For me, recorder was an simple but accurate assessment tool to see who was motivated to play at home and make advancements on their own. Which students wanted more supplemental material, more songs, more etudes? Which students just had a hunger to make music on an instrument on their own terms? Recorder was the answer for that a child. Within three weeks of starting, it was easy to see who's consistently playing recorder at home. That means the teacher needs to be prepared with supplemental material for those kids who are really juiced to play. I’ll wrap up a with a couple of guidelines for recorder management and stoking motivation in “Stacking Skills for Success: Recorder – Part Two”. |

AuthorBoyd Holmes, the Writer Archives

April 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed