But something wasn’t right.

It became apparent that the knowledge they were requiring me to absorb had little to do with teaching in the trenches.

During my junior and senior year, I was hired to be a diocesan band director, overseeing the music education of over two hundred students with a staff of a dozen teachers.

Nothing I had learned my first two years of college prepared me for that job.

And with the exception of the student teaching I did my senior year with Bill Byerly, the band director at Christiana High School, nothing prepared me for life post-college in the world of fulltime teaching.

Very little in college music education prepared me for a career teaching.

Yes, they demand that you attend lots of methods classes, psychology of this, foundations of that – but there is no class called “Ten Years of Experience 101”.

Classes for ONLY 30 or so hours a week? And a week contains 168 hours so that left a lot of time to pursue my own interests?

It was prelude to my concept of the 7.5 hour job and the 16.5 hour business.

I took advantage of these last for years of autocracy before I ventured into fulltime music teaching.

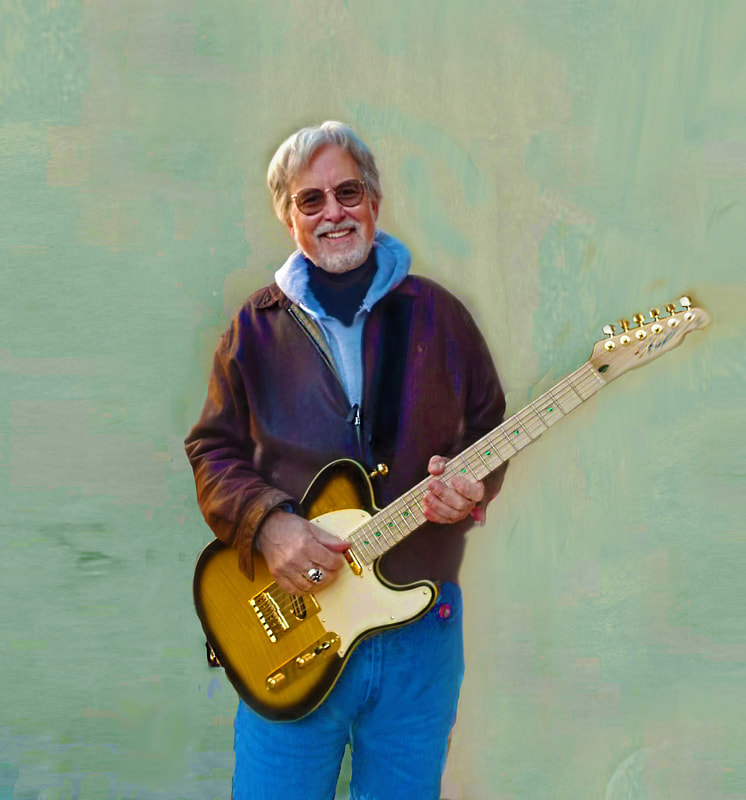

Hiding out in Morris Library, going through the different collections, hanging out in practice rooms, working out progressions, playing a steady stream of gigs on double bass and trumpet – there was nothing better.

How about you?

When you were in college, what was the longest time of performing or teaching that you participated in?

Not practicing (think Iverson) but actual sustained performing or teaching?

What happens when we compare teaching music to playing four to six hours a night under less than optimal conditions?

One of the often ignored educational bonuses of playing in any kind of solo setting or in an entertainment band, a rock band, a wedding band, or a society band is that you have to play for sustained hours at a level where someone is actually going to pay you money for what you just played.

I was gigging from my first days in high school so I had an understanding of sustained playing for money before I got to college. I was able to play and get a “call back” – meaning that I had done a good enough job at an affordable cost to the booker or client that I got return work.

When did you get your first “call back”? How did it make you feel?

I was getting acclimated to playing and singing for longer stretches of times in front of increasingly more discerning ears and wallets.

Playing situations in undergrad college music department were heavily sanitized in controlled environments. Student performance in a college music department, especially if you weren’t a performance major, was very much a boutique experience and one I never found tethered to the real world of employment or cash reimbursement.

“Call backs”? Yes, but that was the extent of it. With each successive year in college, I was gigging more with some of my teachers and with each successive gig, the differences between these two worlds – academia versus the world beyond - became more apparent.

University music reminded me of a terrarium and gigging was more akin to living off the grid in a jungle.

After graduating and teaching full time, I spent several years as a sideman in a variety of groups: orchestras, pit orchestras, after-hours clubs, strip clubs, wedding bands, traveling big bands, and various pick-up bands and jazz trios. Eventually, I co-founded a society band with my co-teacher, Marty Lassman.

Taking a leadership role in an ensemble is a heck of a motivator. Start with the idea of playing in a band and then add on that you're the leader or co-leader of the group and it's like “Lightning Round” on the old TV game show “Password”: the time is halved and the prizes, obligations, and stress are doubled.

Suddenly, preparation, follow-up, and clean-up are much more crucial elements in sustaining an ensemble – as well as maintaining a revenue stream for your 16.5 hour business.

I was required to be "on" for four, five, or six hours at a time with the most minimal of breaks. Add to that a two hour set up and a two hour break down and sudennly we’re talking real work and extended hours.

On summer gigs, it was normal for me to drop three pounds during a gig.

While there were other bands like ours, we saw our biggest competition was ourselves: could we be better than we were a month ago?

Today, society continues to morph the worlds of performance, competition, and entertainment into an unrealistic, synthetic representation of the musical performance arts in the twenty-first century.

Idol this, masked that, America’s got this, lip sync got that.

When kids would come to music class and talk about American Idol or The Voice I would always bring them back to earth by reminding them that those performers were only singing for three to four minutes at a time. Try doing five to six hours, several nights a week, getting paid on a consistent basis, PLUS getting invited back to do it again. Then get back to me and let me know how that's going.

I would remind my students that they performed for longer stretches of time with me in the classroom or chorus rehearsal – and I was always tough on them.

The more I taught in my 7.5 hour job, the more teaching resembled a daily, six-set gig from my 16.5 hour business.

Lucky for me, my strengthened work ethic, perseverance, and endurance originated in my 16.5 hour business perspective rather than from my 7.5 hour job perspective.

Sadly, the mediocrity and tedium that can pass for education in the classrooms of some tenured teachers bears little resemblance to the day-to-day survival of the six-hour-a-night gigging life.

As musicians, we know that we’re only as good as our last gig.

And teachers, you know that means we’re only as good as our last class – especially if its kindergarten.

And usually at least once per gig, someone in the band finds themselves saying, “Whatever it takes” – as in one more song, one less break, or one more hour. Whatever it takes for a successful outcome.

Let me frame it this way: “Whatever it takes”, as in when the Greenville dowager informs you that your playing space in her foyer is currently occupied by a potted twenty-foot tree that she wants the band to move to the other side of the room.

Whatever it takes. (And don’t think that I hadn’t considered that she hired the band just to move the tree because we were cheaper than movers.)

Too often, getting a teaching gig requires a sizable more amount of effort and ingenuity than sustaining a teaching gig. In education, getting the gig becomes “the gig” while the opposite is true when you’re working as a musician in the entertainment field – getting the next gig is second most important thing in your mindset and agenda while playing out.

Let me put it this way: every public paying gig I play parleys into another private or public paying gig. It’s this monetary and artistic vindication that validates that I have been – and continue to be – on the right track in my 16.5 hour business.

That kind of authentication doesn’t exist in the hot-house environment of a school.

Figuring out my 16.5 hour business was key to developing my 7.5 hour brand of education and leadership. Those 16.5 hours informed my 7.5 hours on the importance of what I accomplish in my next twenty-four hours rather than in my previous twenty-four hours.

The rush and rewards you get from creating your 16.5 hour business persona will often carry you through affirmation droughts that can occur in a school setting.

I you haven’t started seriously examining your potential for ongoing success in a personal 16.5 hour business, start the process today.

Yes, the hours aren’t as regimented as your 7.5 hour teaching job and some days, you’ll be working more than hours than you ever imagined you could.

It will make those five hour stints in college (as well as your 7.5 hour job) feel like a cake walk.

There is no rule book or instruction manual for the life you want to create. But hey, that’s half the fun.

After all, there is always more room for success in your life.

Whatever it takes, right?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed