|

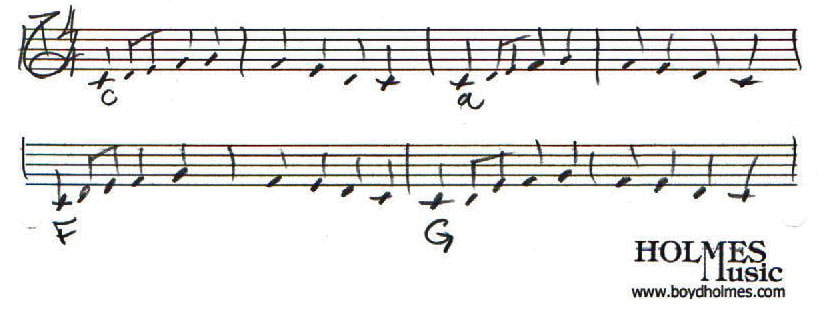

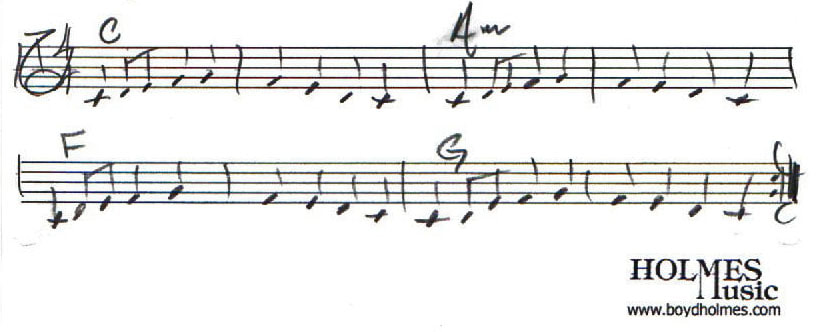

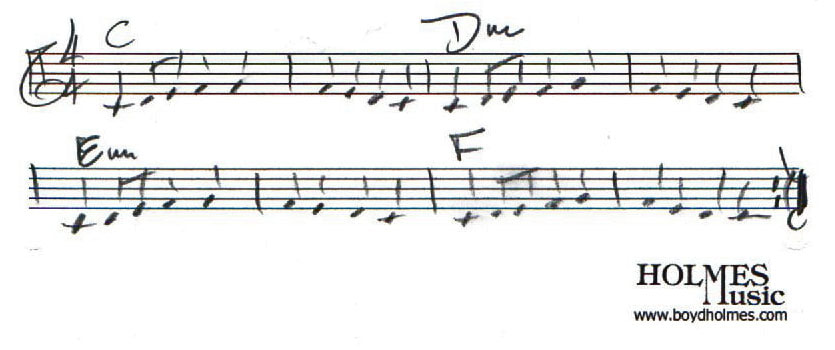

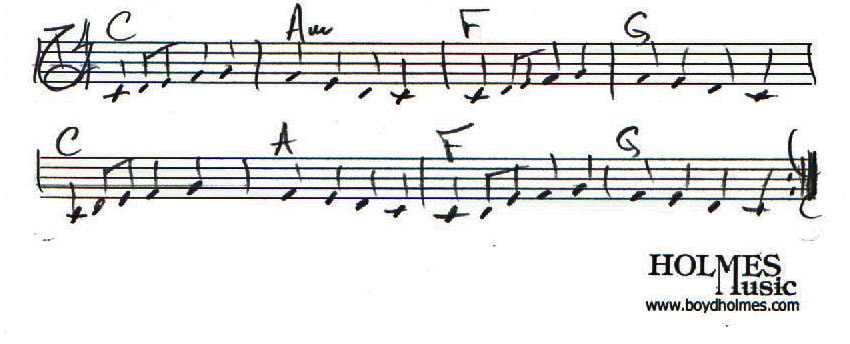

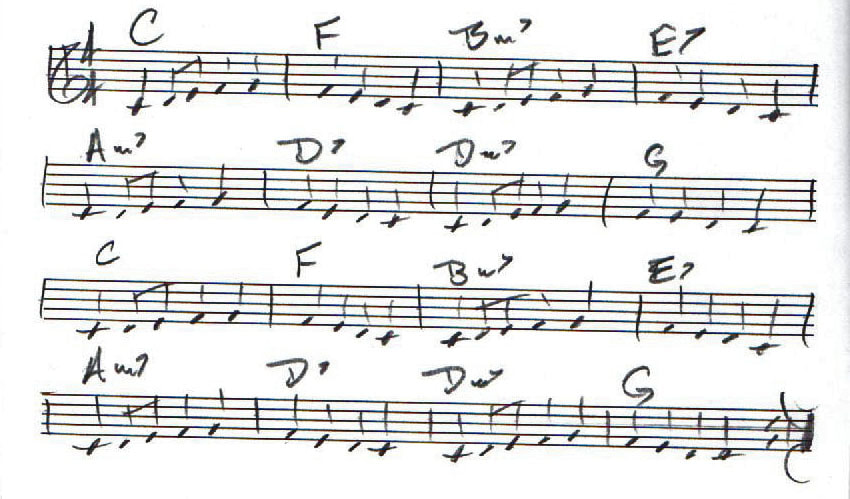

If you haven’t been following along in part one, two, or three, check them out before progessing. So here’s a little exercise to get the pencil moving. Take one of the songs you previously copied. In each measure, circle the notes that can be found in chord that is over that measure. Scat the song with the chord tones at ff and the non-chord tones at p. Notice how most of the notes in the melody are in the chord. Now, let’s move to the piano and scat the same song as we normally would while we play the letter name of the chord either as half notes, whole notes, or with a slight repetitive rhythm. It’s not just enough to move the pencil while writing a monophonic melody. The melody needs to be grounded to a harmonic progression, just like the melodies in the songs you copied were anchored to a chord progression. It’s time to address the chicken and egg conundrum: what comes first - the melody or the chord progression? The basic is answer is that they occur simultaneously. The melody is structured around chord tones. We’re going to “cook book” our first melody/chord progressions to get our feet wet and our pencil moving. Imagine you need to write a two bar practice etude for a young trumpet student. The trumpeter knows quarter, half, and whole notes as well as the pitches C, D, E, F, and G. If you played an instrument as a young child or took a methods class in college, you probably played an etude in your first book that fell into these parameters. Take your pencil, write your treble clef, 4/4 time signature, and then write those five notes in an ascending line starting on C up to G and directly back down to C. Let’s make them all quarter notes. Make sure you scat them as you write them. Scat with a loud voice! By now, you have probably noticed that nine quarter notes are one beat too many for two bars. There’s an easy fix. With the exception of the very last beat, the low C, make any two consecutive notes of the first seven notes eighth notes. Success! You should have an exact two bar phrase – seven quarter notes and two eighth notes ( I put my two eighth notes on the second beat of the first measure). Ok. Scat it. Do you like it? Let’s try some editing. Think about position the two eighth notes somewhere else in the two bars. Scat it as you write it. Which version do you like best – the first or second? If one sounds a lot better than the other, go with the one you like. If you still think there might be a better place for those eighth notes, keep experimenting by moving the eighth notes while writing and scatting. We’re looking for the version that sounds most natural when we scat it. Found the best two bar version for you? Great! On a new sheet, write out your two bar phrase four times in a row to create an eight bar etude. Scat it as you write. Remember, loud! Next, we are going to write a bass note under the first notes of the first, third, fifth, and seventh measures. The four bass notes will be C, a, F, and G. Give yourself a little four bar C bass ostinato intro before you scat your melody while playing the bass notes. Imagine your trumpet student playing this etude while you give him a neat little bass rhythm on the piano. Groovy! Let’s flesh out those bass notes to full chords; C, a , F, and G. An “A minor chord” is symbolized by a lower case “a”. All lower chase chords will be minor. Write the eight bar melody again but this time, write the chord names over the first notes of the first, third, fifth, and seventh measures. Scat the etude again while you play whole note chords in your right hand with a simple ostinato bass part in your left hand. Change the final single bar line into a repeat sign. This thing will now give “This Is the Song That Never Ends” a run for its money. Play it over and over as you scat the melody. No matter how easy the melody is (and it is very easy), keep reading it as you scat it. Stop – and softly scat the melody while you THINK about the sound of the bass and chords. You won’t necessarily hear the chords in your mind – but I bet you will feel them and get a different sensation as your eye tracks through each note in your head. Now write out your melody with new roots under each successive two bar phrase: instead of C, a, F, and G, let’s use C, D, E, and F. Scat it with these bass notes on the piano. Feels different, right? Instead of a C, Am, F, G progression, we’ll use these bass notes to anchor a new progression: C, d, e, and F. Try all these chord progressions. Slash chords like F/G means play an F major chord over a G bass note. Scat and play the melody and progression loud two times in a row followed by softly scatting it a capella and feeling the harmony as you scat: C, am, F, G Cmaj7, am7, Fmaj7, G7 Cmaj7, am7, Fmaj7, F/G C, dm, em, F Cmaj7, dm7, em7, Fmaj7 am, em, F, E am7,em7, Fmaj7, E7/G# Let’s try accelerating the harmonic rhythm. Instead of two measures for each chord, lets switch chords every measure. Write out our eight bar phrase and double it to sixteen bars with a repeat sign at the end. Scat while you write. Try this eight bar progression with one chord per measure. C, F, b, E, a, D, d, G

Cmaj7, Fmaj7, bm7, E7, am7, D, dm7, F/G C, G/B, Am, G, F, em7, dm7, F/G Let’s use our old pattern of two times with piano nice and loud and then softly while you audiate the harmony. We’ll finish this exercise in “The Songwriter’s Notebook: “Keep Your Pencil Moving” Explained – Part Five” "If you can’t say it, you can’t play it!”

Each of the million times I said the first half of that phrase to my class, kids would scream the second half back to me. Recorder in third grade is the perfect way to solidify the “trifecta: say the rhythm first, say the pitches second, and say the fingers and move them with an invisible recorder, third”. It Is always better to break down big goals into little skills. The recorder should be positioned in their laps – not their hands - when doing the trifecta. Do each of the three trifecta passes of an etude while you are pointing to the notes on a SmartBoard. On the first pass, have them chant the rhythm “Quarter, quarter, half-, note, whole-, note, three, four”), the pitches on the second (“B,A, Beeeeeeeee,Geeeeeeeeeeeeee”), and the fingerings on the third (One, One and two, Oooooone, One-two-and-threeeeeeeeeeeee”). Only after accomplishing the trifecta, does the instrument even approach the mouth. After kids have done the trifecta a few dozen times out loud with their recorder, give them the previous prompts but have them do it silently as you continue to point to the notes. Make sure they are tracking the notes with their eyes. The next step is to give the prompt and not point and watch them silently do the trifecta with only their self-disciplined eye point. Rhythm, pitch, and fingering will quickly become imbedded skills and the trifecta process will fade while spontaneous reading and performance will appear. Teaching with the trifecta model is the easiest way to assess and predict if a kid will be able to play an eight-bar etude. “If you can’t say it, you can’t play it!” A recorder is often the first instrument a child owns.

They have to learn the practical applications of responsibility: cleaning it, practicing it, putting it in their backpack the night before they need it in music class, and self-control (as in the right places to play). If you haven’t checked out Part One and Part Two, best to do that before you go on.

Let’s give the pencils a break. Many of you are connecting the dots that I have provided concerning the idea of basic audiation skills. For those not familiar with the word, audiation refers to the ability to mentally hear sounds before they enter a physical realm. When I say “keep the pencil moving, I mean “keep writing down the sounds you hear in your head” – and that entails audiating. Anything else is just a poser's creative two-dimensional art. There are different audiation methodologies that are taught that sequentially develop these skills. Many music education majors are formally introduced to audiation with Edwin Gordon’s techniques. Some have been exposed to it in elementary, middle, or high school. It’s best to address this issue before I go any further. Time for a story. Is it similar to yours? How I Learned To Audiate I started to audiating started when I was very young. To say I was imaginative as I developed into a five-year-old is an understatement. I was constantly drawing, singing, doing puppet shows, and hearing music in my head – in general, deeply involved in imaginative, hands-on play. From my earliest memories, when I listened to music, I imagined colored lines moving left to right in my mind. Each line represented a different instrument or voice. As the pitches rose or fell, the lines responded like-wise. I don’t know if anyone talked to me about doing this or if I created this pastime as a diversion like I did with so many other activities as an only child is inclined to do. By the time I was five, I knew how to operate our turn-table that was hooked to our RCA TV audio speaker. I would put on an album and draw the lines as I listened to music. I repeatedly listened to something like Leroy Anderson’s “Belle of the Ball”, first follow the flute part and draw their line in blue, move the needle back to the beginning, and then do the trumpet line in red, until I had a mess of colored-pencil lines becoming “my creation”. These works of art were my first scores. Even when the LP wasn’t playing, I could hum each of the parts from memory and do a new colored-pencil score of lines that was as accurate as the original. I believe that the roots of audiation develop much like those for perfect pitch; namely in our earliest years. These foundational skills grow no from a rigid set of rules, hierarchical architecture learning strategies, or “work” but from open-ended cross-disciplinary imaginative play. While perfect pitch rarely if ever develops beyond childhood years, audiation can. I had no formal music instruction in my elementary school. In fourth grade, I started my musical journey with trumpet lessons. I was very fortunate to reinforce these audiation skills as a young trumpet player. I always sang the studies I had to play. I treated it like a game. I loved singing my etudes while fingering the notes to my etudes and Herb Alpert hits on an invisible trumpet. When I say “sing”, it was more sotto voce rather than full throated singing. In fifth grade, I found a huge up-for-grabs stack of blank manuscript in my band room and started the habit of writing out my favorite songs, TV themes, as well as a few originals. (I still occasionally find myself absently minded finger melodies with trumpet fingers.) In elementary and high school, I usually played second trumpet in band. As I practiced my part, I could always hear the first trumpet part in my mind as I played the second part on my horn. Melodies are horizontal and while I thought hearing one or two notes simultaneously was easy, I knew there had to be a systematic way to accurately hear horizontally – but I was clueless. Clueless, that is, until I started playing double bass. It didn’t matter if it was pop, jazz, or folk mass, when I played bass, I was following vertical chord progressions that were always rising over a line of melodic notes and supported by rock-sold guitarists or pianists. Playing roots and fifths on bass will only get you so far with a lot of material. I had to learn how to arpeggiate chords in several positions. Listening to the basslines of Paul McCartney, Ray Brown, and James Jamerson were great role models. I was accurately audiating a cantus firmus double bass on the bottom and a trumpet in the melody over a bed of chords. Before I knew it, I was able to contrapuntally hear the melody as well as a counter-melodic bassline to songs in my head as I rode the city bus to and from high school. Mind you, I had no vocabulary for what I was doing. I was just doing it. Every weekend, I played double bass in two folk masses that featured some advanced harmonic songs. At times, it was “suggested” that I sing a harmony note to bolster the singers. I was audiating the melody on top, the bass on the bottom, and my improvised harmony part in the middle. It was all still play. In my mind’s ear, I remained shaky on the notes in between. Major and minor, as well as the inner voices) created a different sensation in my mind’s ear while the melody or bass were more visually solid. Occasionally I would write these things I heard in my head – but I wasn’t driven to constantly write because I could play what I heard and had developed the ability to accurately predict what a line of notes would sound like before I played them. I was too busy writing out jazz band charts and copying parts, singing them as I reduced pencils to little wooden stubs. My parents were happy. I at least gave the appearance of being industrious. They were so approving of my efforts that they bought me the book that I had wanted for a long time: Henry Mancini’s “Sounds and Scores”. I was now able to listen to snippets of Mancini’s work while following the score with detailed explanation of his orchestration choices. I put almost all high school academic work on hold. After all, I was too busy writing out jazz band charts and copying parts and making those little wooden stubs. By the time I got to college and freshman year “Music Reading and Ear Training” and music theory class, I was on cruise-control. Back to the pencils in “The Songwriter’s Notebook: “Keep Your Pencil Moving” Explained – Part Four”. |

AuthorBoyd Holmes, the Writer Archives

May 2025

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed