I had a policy in my classroom where I kept number 10 posted on my chalkboard at all times. If I saw some serious problems in the class, I would not smile, I would say very little, usually nothing at all, and simply erase the 10 and replace it with a 9. If the class dropped down to a 9 or an 8 but responded properly, as in they turned on the gas jets attempting as a united class to improve, I would say nothing but would raise the number up one digit. As a result, the goal was always to have a 10 at the end of class.

The students knew I always reported that final number to their teacher when they were picked up. The teachers supported the expectation that their class would earn and keep at 10 at the end of class.

There was one incredible way to get an 11 in my class. The way a class got an 11 was to stand up quietly when a visitor walked into our room. It didn’t matter if it was another teacher, a first grader, a grandparent, the custodian, a cafeteria lady – they come in, we stand.

Pretty simple. Nothing needs to be said. Nothing to do but just stand up and smile with teeth. “Because”, I would say, “this is a sign of . . . .?” And they kids all would say, “Respect!”

I would tell them that if they didn't feel like standing, they didn't have to stand but if one kid did not rise, the 10 did not change to an 11. And if they were on a 9 when they stood for a visitor, the number would only go up one digit to 10 – so if they wanted an 11, they knew they had to be on a 10.

I counseled them that if everyone was standing except the kid next to them, the idea was not to slap the kid in the back of their head to get them to stand but rather to gently get their attention and point to the fact that everybody was standing.

If, and only if everyone was standing, quietly, smiling, showing their teeth (because that's the only real smile - a smile where you see your front teeth – and they better be clean) when the visitor would leave, I would change their 10 to an 11 and we would all celebrate with a freeze pop party.

Due to medical and dietary reasons, not everyone was allowed to have a freeze pop. And in some schools you're not allowed to give any edible treats to kids at all. I was able to do the freeze pops in my school. I bought them at Costco, and the $8.00 I sent on 200 freeze pops was money well spent. Ahead of time, I would parcel out the 200 freeze pops into piles of 20, put them in a grocery bags, secure them with a rubber band, and keep them in the teacher’s lunch room refrigerator freezer for quick access.

When we had reason to celebrate an 11, the kids were ecstatic. And I would allow their screaming and shouts of joy once I told them we were going to get a freeze pop party. I praised them for their sign of . . . “Respect!”

The first thing I had to do was check to see if there were kids that we're not allowed to have sugar or freeze pops. I would tell those kids that they would get something special instead of a free spot from me. Usually three Mr. Holmes guitar picks.

We would line up at the door to go to the teacher’s lunch room with one caveat: I would tell the kids that if one - and I meant one - if one kid started walking without their hands behind their back or started talking in the hall, I was simply going to stop the line and take them back to our music room and there would be no freeze pop party that day. Not that they lost the party forever. It would mean that we would have wait and try again on another music day. As I would say to the older kids, “This is not the day you want to learn what ‘delayed gratification’ is. Get it right the first time.”

Most times we did it perfectly: we'd hit that hallway, walked to the teacher’s lunch room, grabbed the correct numbers of freeze pops, headed back to the music room, partied on “Go” time with their choice of music on the SmartBoard.

But there were days when they found out that I was a man of my word. If they couldn't get down the hallway properly, there would be no yelling or screaming from me. I would simply turn the line around around and we walked back to my room and sit down quietly for a good two minutes in silence thinking about how good those freeze pops would have tasted. I would break the silence by saying we'll try again on another day. Failure to get to the teacher’s lunchroom never occurred twice with the same class.

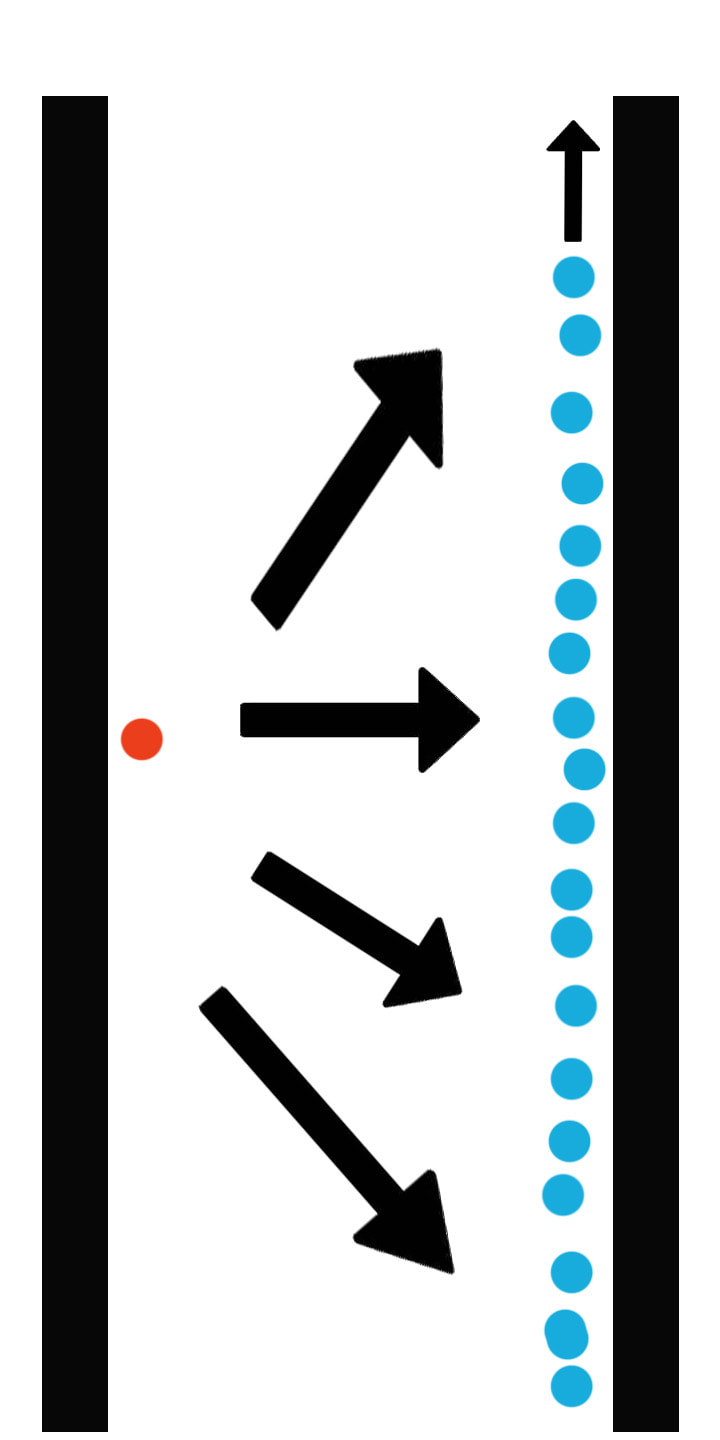

As kids approached fourth and fifth grade, sometimes when they were in line, I'd say, “Funny how life can sometimes be all about getting from here to there, isn’t it? As we get older, accurately and safely getting from here to there can be very important. Think about what we look like getting from here to there. What will people say as they watch us moving from here to there?

Knowing the best way how to get from here to there will have a lot to do with how successful we’ll be in achieving our goals.”

None of this had nothing to do with music. They didn’t remotely approach topics like this in any music education classes.

"Getting from here to there" has to do with children developing self-discipline, planning, setting and re-assessing a goal, and feeling good about their accomplishments.

Just as small things lead to big things, small kids turn into big adults. Getting from here to there is probably one of the greatest existential skills I developed with most of my students.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed